Before his epic fall, Sam Bankman-Fried was hailed as a crypto genius. Some clients saw smoke and mirrors.

Until a few days ago, Sam Bankman-Fried was the king of crypto.

A 30-year-old MIT graduate with a net worth of $16 billion, according to Forbes, Bankman-Fried ran a top crypto exchange called FTX, counted NFL legend Tom Brady and NBA superstar Stephen Curry as company ambassadors, emblazoned FTX’s name on the Miami Heat arena and donated millions of dollars to lawmakers, mostly Democrats. He regularly wowed much of the financial press. “The Next Warren Buffett?” Fortune Magazine asked on a recent cover.

Now, his Bahamas-based empire is scorched, investors are shellshocked and the entire crypto ecosystem is on edge. FTX and an array of related entities filed for bankruptcy protection on Friday morning, Bankman-Fried resigned and a new CEO has been installed to oversee a process to “maximize recoveries for stakeholders.”

The meltdown began last weekend and accelerated Tuesday when FTX International halted customers’ redemptions. A major investor threatened to sell because the company’s financial soundness had come under scrutiny and the ensuing market mayhem took the price of bitcoin to a fresh low this week.

“I’m sorry I didn’t do better,” Bankman-Fried said Tuesday in a message to investors reviewed by NBC News.

On Thursday, he posted on Twitter that he was fighting to “bring liquidity to users.” Bloomberg News reported that FTX and Bankman-Fried would need $8 billion to make up the shortfall, and that the Securities and Exchange Commission and Justice Department are investigating whether the firm handled customer funds properly (both declined to comment to NBC News).

A banner posted to the FTX U.S. website on Thursday said trading may be halted in a few days and advised users to close down positions. Friday morning brought news of the bankruptcy filing.

Bankman-Fried’s stunning fall from grace was the latest in a series of crypto crackups this year that included the demise of the Terra Luna token and the Three Arrows Capital crypto hedge fund, liquidated in June. Taken together, they amount to a monumental collapse for a once-hot industry hyped by many investors and technologists who invested millions, accrued assets that became worth billions, and are now looking at stressed balance sheets.

But three people who have dealt with FTX, its executives and its related trading firm Alameda Research, say this debacle differs from other crypto failures. That’s because Bankman-Fried’s operation involved two closely-tied entities: one, the large crypto exchange in which investors could trade an array of tokens and derivatives, and the other, Alameda Research, the big trading firm that profited by making markets in crypto and derivatives. This meant not only matching buyers and sellers, but also using its own money to trade.

One investor and two executives at a client who did business with Bankman-Fried, FTX and Alameda, in recent years, told NBC News that they lost money in what they contend were manipulative trading activities. Their allegations raise questions about whether conflicts of interest inherent in the arrangement between FTX and Alameda may have generated profits to the firms while harming investors.

When a market maker and an exchange are owned by the same entity, it raises concerns that the market maker could see other investors’ trades before they are executed, allowing them to trade ahead of them at a profit.

The contentions of the people who spoke with NBC News are echoed in a 2019 lawsuit brought in federal court against FTX Alameda, Bankman-Fried and other executives.

The plaintiff, an entity called Bitcoin Manipulation Abatement LLC, accused the defendants of manipulating crypto markets, causing $150 million in losses to “numerous cryptocurrency traders.” The company moved to dismiss the case, and the suit was dismissed with prejudice, a court filing shows, indicating a settlement was struck. The lawyer for the plaintiff did not return a phone call seeking comment.

“This is someone who has been able to skate through on money and power,” Ben Armstrong, creator of BitBoy Crypto, a YouTube channel with 1.4 million subscribers, said of Bankman-Fried. “This man needs to face everything he has done — he can’t wriggle out.”

Bankman-Fried, known colloquially as SBF, did not respond to an email seeking comment.

‘The cleanest brand in crypto’

Bankman-Fried’s brief history in finance has been recounted in countless news stories, most of them gushing. After graduating from MIT in 2014, according to the reports, he joined Jane Street Capital, a New York investment firm that trades equities, bonds, options, exchange-traded funds and cryptocurrencies.

He incorporated FTX Inc. in 2013, Delaware records show. He left Jane Street in 2017 and opened FTX for business in 2019 as an exchange for trading crypto and associated derivative products, such as futures on bitcoin and tokens.

Over the years, Bankman-Fried, who favored a uniform of T-shirts and cargo shorts, raised almost $2 billion from savvy institutional investors, according to The Block, an information services company that specializes in digital assets. They included Tiger Global, a hedge fund in New York, Sequoia Capital of Menlo Park, California, and Temasek, a global investment fund in Singapore with approximately $300 billion in assets. A spokesman for Tiger Global declined to comment; Temasek did not respond to an email inquiry and Sequoia posted a note to investors on Twitter late Wednesday saying it had written down to zero its $150 million investment in FTX.

As 2022 dawned, FTX was on a roll, valued at $32 billion.

FTX and Bankman-Fried had cultivated high-profile people and projects. Star quarterback Brady and his then-wife and supermodel Gisele Bündchen became ambassadors for FTX, and reportedly received equity in the company. In June 2021, the company announced a deal with MLB that placed the FTX logo on all umpires’ uniforms.

A company sales pitch to potential investors earlier this year highlighted these efforts.

“FTX has an industry-leading brand, endorsed by some of the most trustworthy public figures, including Tom Brady, MLB, Gisele Bundchen, Stephen Curry, and the Miami Heat, and backed by an industry-leading set of investors,” boasted the document, obtained by NBC News. “FTX has the cleanest brand in crypto,” it said.

But the crypto market does not have the protections or price transparency found in listed stock markets, for example.

FTX and Alameda, as a major crypto exchange and market maker, attracted crypto developers to list their projects for trading.

One was Hussein Faraj, chief executive of NuGenesis, an Australian blockchain company. Faraj, a decentralized ledgering system architect and blockchain forensics expert, struck a deal in 2022 with Alameda to support the launch of NuCoin, a crypto project he and his partners had been working on.

Alameda represented itself as a partner to the NuCoin founders, Faraj said, a market maker that would help NuCoin gain traction with investors in the crypto market.

“The market maker is someone who comes in to support you,” Faraj said. “At the start of any project, during the first month, you will need support.”

To gain that support, a contract reviewed by NBC News shows, NuGenesis agreed to loan Alameda 200 million NuCoins for two years. At the end of the period, Alameda would either return the coins to NuGenesis or buy them from it at 38 cents each.

Faraj expected that Alameda would support the price of NuCoin in a narrow band, as its agreement with Alameda had stated.

Instead, Faraj said, over a short period, Alameda dumped huge numbers of the coins onto the market at a depressed price.

At the same time, Faraj said, when he tried to buy NuCoin to counter the selling pressure, Alameda prevented NuGenesis from doing so, effectively destroying confidence in the project.

“With his exchanges, he prevented genuine buyers—including ourselves—from restoring the price,” Faraj said of Bankman-Fried. Faraj said Alameda later confirmed to NuGenesis that it had dumped 800,000 NuCoins on the market.

When NuGenesis threatened to sue FTX, it offered to pay $600,000 to settle, according to an email to Faraj from Alameda reviewed by NBC News. “This represents a windfall to you but we want to end this dispute and not hear from you again,” the email stated. The offer was refused.

Faraj’s allegations were confirmed by his partner.

Amid the FTX collapse, Armstrong, the Bitboy Crypto creator, said: “Every enemy SBF has ever had has reached out to me.”

Seeking a ‘retail base’

Earlier this year, when FTX was riding high, it had “one major weakness,” the investor pitch document said. It needed to increase the number of individual investors using its exchange. FTX had 150,000 monthly trading users and 5 million registered users, roughly 3 percent the user base of its larger competitors.

“We can, and will, keep growing out our consumer userbase — both organically and through paid advertising,” the document said. “But it would be massively valuable to acquire those users much more quickly.”

The experience of Dave Mastrianni, a former crypto enthusiast who is a retired web designer and artist in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, indicates what can happen to a trusting individual investor who followed Bankman-Fried’s lead in the crypto markets.

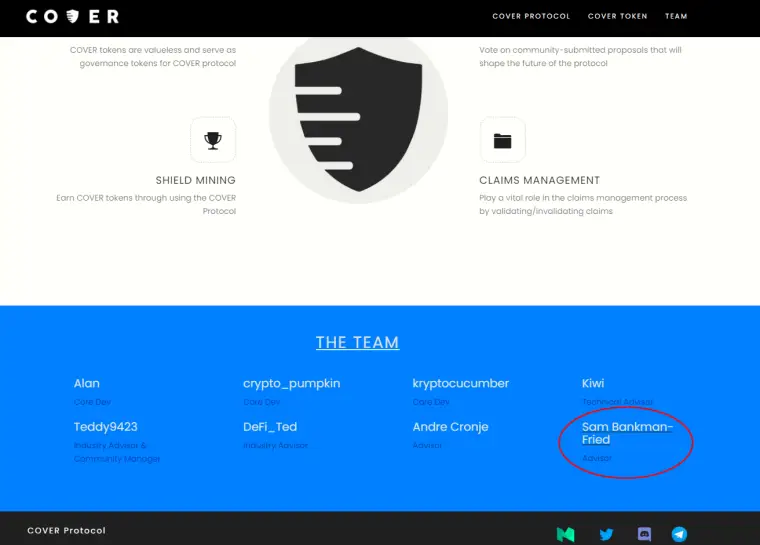

Mastrianni, 64, who became disabled during basic training as a U.S. Marine in Parris Island, liked what he’d heard about crypto and in 2019 started investing the money he’d saved. One of his investments was a crypto token promoted by Bankman-Fried called the Cover Protocol. Mastrianni took about $10,000 and bought into the token in 2020, he said.

“If you’ve got an exchange like FTX and you’re global, people think you’re a person of integrity,” he said. “I ended up buying because Sam’s name was on it.”

The token took off after Mastrianni bought, but when he tried to cash out, he said he could not get his transaction executed. A message would pop up stating: “Insufficient liquidity for this trade,” he said.

"I tried to sell when I was up $300,000 and $400,000," he said.

Soon, the token crashed, wiping out all his paper profits.

Mastrianni described what happened to him as a pump-and-dump scheme, and his allegations are similar to those in the 2019 lawsuit, which accused FTX, Alameda and Bankman-Fried of conducting such schemes to mislead and profit off crypto market participants.

On Oct. 13, 2020, Mastrianni emailed FTX asking about Bankman-Fried’s role as an adviser on the decimated token, according to an email reviewed by NBC News. The next day, Dan Friedberg, FTX’s chief regulatory officer, responded, asking Mastrianni to discuss his issues on a call.

When they spoke, Mastrianni said he tried to talk about recouping his losses, but Friedberg steered the conversation in another direction: offering him a job at FTX as a graphic design consultant, creating artwork that could be sold as non-fungible tokens or NFTs.

“I told him, ‘Sam was involved in a pump and dump,’” Mastrianni recalled. “He said, ‘We’re not going to talk about that, we’re going to talk about you being an adviser to FTX.’”

At the same time Friedberg sent him an employment agreement to sign and offered to pay him one bitcoin for 30 days of work. But the agreement, which NBC News reviewed, contained language stating that Mastrianni acknowledged FTX, Alameda and its affiliates were not responsible for his losses in the Cover Protocol or his other crypto investments. Still angry over his losses, Mastrianni said he refused to sign.

Then, in April 2021, he agreed to the contract, receiving one bitcoin from FTX. He started creating designs for the company as he’d promised but said FTX did not accept his work. He says he didn’t hear from the company again until Friedberg sent him an email in July 2021, reviewed by NBC News, saying “the bitcoin payment was primarily for your release of all claims.”

Friedberg did not return an email seeking comment.

“They strung me along, trying to get me all excited about being an adviser,” Mastrianni said. “But the truth is, it was all about” the settlement.

As he scaled crypto’s heights, even attaining multibillionaire status, Bankman-Fried made clear to interviewers that he planned to give his entire fortune away. According to a May profile in The New York Times, he said he believed in what’s called “‘earning to give’ — a model in which do-gooders devote themselves to lucrative careers, aiming to earn as much as possible before giving it away.”

“My goal is to have impact,” he told an interviewer from Forbes.