Biden's union bonafides are tested with the autoworkers strike

WASHINGTON — Democratic officials in Michigan came up with what they thought was an inspired plan: They invited President Joe Biden to a rally in Detroit on Labor Day, hoping he would lend support to autoworkers ahead of a looming strike, people familiar with the matter said.

Biden turned them down, these people said. Instead of going to Michigan, a state he has visited six times during his presidency, he made his 27th trip to Pennsylvania for a Labor Day appearance where he told reporters he didn’t believe the strike would happen.

His comment baffled some Democrats, who were bracing for that very outcome, and the president turned out to be wrong. Contract talks quickly collapsed, and the following week the United Auto Workers union launched its strike against the Big Three automakers — General Motors, Ford and Stellantis.

Skipping the Detroit event was a “lost opportunity” for Biden, a Democratic member of Congress said in an interview.

Now, with the strike entering its second week, Biden has decided to visit Michigan on Tuesday to show his support for the UAW, according to two people familiar with his schedule. The shift in plans follows several days of discussions inside the White House about whether Biden should make the trip after his top rival in the 2024 campaign, former President Donald Trump, announced he would visit Detroit on Wednesday to see the autoworkers.

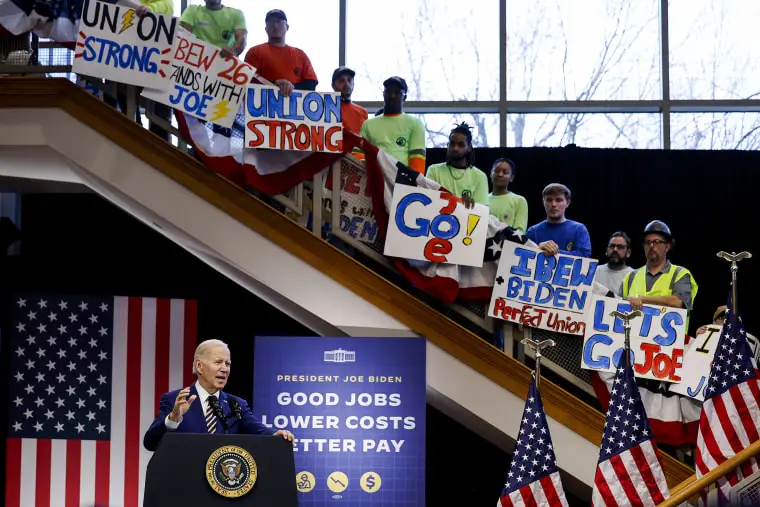

Biden's plan to go to Michigan also comes as he struggles to carve a meaningful role for himself in a crisis that could damage his re-election prospects. Biden boasts that he’s the most “pro-union” president in memory, yet a prolonged strike would test that claim and threaten to jeopardize the economic gains that are the core of his 2024 campaign message.

On Friday, the UAW invited the president to join its picket line. People familiar with the White House discussions about whether Biden should go said one concern that was raised was that the more he inserts himself in the conflict, the more he owns it — for better or worse.

“If the president wants to walk the picket line, that’s his right,” said former Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, who has discussed the contract dispute with both the White House and the union. “But that doesn’t settle a contract. That shows support for workers.”

In the first week of the strike, economic losses topped $1.6 billion, according to Anderson Economic Group, an economic consulting firm. The cost is expected to mount. Chances of a swift settlement dimmed Friday, with UAW President Shawn Fain announcing that the strike was expanding and that workers at 38 GM and Stellantis distribution centers would also be walking out.

Biden’s early attempt to inject a pair of senior administration officials into the dispute by sending them to Detroit backfired when the union gave word that it didn’t want them involved, people familiar with the matter said. The plan to send acting Labor Secretary Julie Su and senior White House adviser Gene Sperling to Michigan turned out to be premature, a person familiar with the White House’s strategy said.

“This is our battle,” Fain told MSNBC this week. “This battle is not about the president, it’s not about the former president or any other person prior to that," he added, referring to Trump.

Republicans are divided on their approach to unions, with many elected officials and presidential candidates positioning themselves as traditional anti-union conservatives. But Trump plans to speak with union members in Detroit Wednesday while the rest of the Republican field debates in California, and he is so far the only GOP candidate with plans to address the autoworkers.

Biden risks being one-upped by Trump, his main rival in the 2024 presidential race. Having won 40% of union households in the 2020 election, Trump looks to make more inroads with this voting bloc by heading to Detroit and addressing UAW members.

Trump's efforts to seek out autoworkers and others in organized labor underscores the attention he's paying to blue-collar voters in Midwestern swing states, one of his top advisers said. It's a slice of the electorate that powered Trump's victory in 2016. Those same states then helped defeat Trump and propel Biden to the White House four years later.

"He’s saying, ‘Hey, I represent your members. I’m the one who’s going to protect your jobs and not get them shipped off to China or shipped off to other states," the top adviser said.

Biden allies depicted Trump’s move as a cynical ploy to win over a labor constituency that suffered under his tax cut program.

The White House says that it does not see its role as mediating the dispute and does not want to take part in the negotiations.

“President Biden knows that collective bargaining works and his administration stands ready to assist in whatever ways are helpful to the parties," Robyn Patterson, a White House spokesperson, said.

In addition to heading to Detroit, Biden is scheduled be out West for part of next week, raising funds for his re-election campaign and attending official events that include a speech about democracy.

Economic losses in the first week of the autoworkers strike were largely felt in Michigan, Ohio, Missouri, Kansas, Indiana and Alabama — states that are home to plants that have been shut down, according to Anderson Economic Group.

Biden can ill afford to see those losses grow. That's part of the reason his aides say he's navigating the dispute carefully, not wanting to alienate either side. Biden is calling for a new contract for the UAW’s 143,000 members that amounts to a “win-win.” His position is that “record corporate profits should lead to record UAW contracts,” Patterson said.

“I never remember a president of either party saying with such clarity where he stands on the question of collective bargaining in the middle of a strike” said Rep. Dan Kildee, D-Mich. “The president was clear that he stands with the workers and believes the companies need to do more. That’s a remarkable statement and one that’s unusual and very welcome.”

Yet Biden’s sympathies run both ways. He spent 36 years in the Senate representing Delaware, a state that has “more corporations incorporated than every other state in the union combined,” he said at a campaign fundraiser two days before the strike began. “So, I’m not anti-corporation.”

Nor are corporations anti-Biden. GM donated $500,000 to Biden’s inaugural committee fund, while Ford contributed $250,000. During a visit to a GM plant in 2021, Biden called the company’s chief executive officer, Mary Barra, an “incredible leader” and praised GM’s commitment to building the electric vehicle charging stations that are part of the White House’s renewable energy agenda.

By contrast, Biden seems to have little personal chemistry with Fain, a labor leader in the progressive mold of Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt. Some rank-and-file union workers seem wary of Biden’s centrist, split-the-difference orientation. Fresh in their minds is his handling of a threatened rail strike during the holiday season last year.

Biden signed a bill that averted a strike and gave workers a pay raise but denied them the paid sick leave they had wanted. The compromise prevented a crippling rail strike but drew protests later that day when Biden showed up in Boston for an event.

“Biden has no business getting involved with our business,” Brian Keller, a UAW member, said in a recent interview outside the Stellantis North American headquarters in Auburn Hills, Mich. “This is a private sector. If Biden does to us what he did to those rail workers, he would lose the support of the UAW.”

At this point, Biden can’t afford to lose support from anywhere. Polls show he is running about even with Trump. And the union households who backed him over Trump by 56% to 40% seem to have cooled on his presidency. A NBC News survey during the midterm elections last year found that 52% of union households disapproved of Biden, compared with 48% who approved.

Source: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/joe-biden/bidens-union-autoworkers-strike-trump-rcna111379