California hotel workers on strike demand higher wages and a chance to live closer to work

ANAHEIM, Calif. — A second wave of hotel strikes is hitting Southern California this week.

Hotel workers and labor organizers have been striking and demanding higher wages and other benefits as they argue their existing salaries are unsustainable amid the region's high cost of living and rent, making commutes and buying basic goods unsustainable.

Irene Andrade, 53, has worked as a housekeeper at the Sheraton Gateway next to Los Angeles International Airport for 17 years. She used to live in nearby Inglewood, but she moved to Ontario in San Bernardino County to be able to afford rent. She said she spends several hours commuting to and from work — she's on the road at 5 a.m. and gets home around 7 p.m., and she hardly gets to see her 7-year-old daughter.

“It’s very important for me, but I have to fight to get ahead. I’m losing here to go work,” she said about her inability to spend more time with her family, “but I have to.”

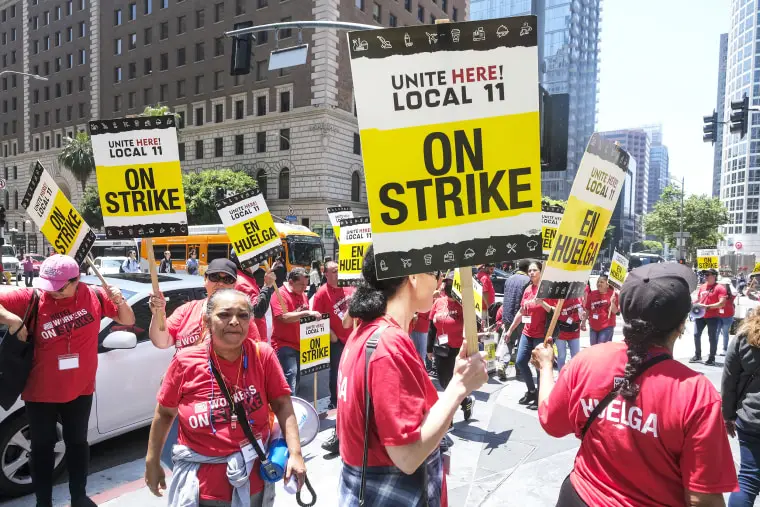

Unite Here Local 11, which represents more than 32,000 hospitality workers across Southern California and Arizona, many of whom are Latino and people of color, coordinated the latest multiday strikes affecting at least 12 hotels Monday and Tuesday near the Los Angeles airport and cities in Orange County.

Thousands of hotel workers participated in three-day work stoppages last week that affected 21 hotels in downtown Los Angeles and Dana Point during the long Fourth of July weekend.

Sixty hotel contracts affecting 15,000 hotel workers, including front desk clerks, uniform and room attendants, restaurant workers and more, expired June 30.

The union has been in contract negotiations since late April. It is asking for an immediate $5 hourly wage bump and a $3-an-hour annual increase across two years, along with health care benefits; a pension; a policy against the use of E-Verify, the federal system used to check work eligibility based on immigration status; and safer workloads, among other conditions.

According to the union, the changes would help cover expected rising costs in the region ahead of the 2026 soccer World Cup and the 2028 Summer Olympics.

Rising costs, heavier workloads

Arturo Huezo, 52, a housekeeper for 29 years at the Fairmont Miramar in Santa Monica, said he has been through about seven contract negotiations and has never been compelled to strike.

But he said he has experienced the steady and rising cost of living in Los Angeles and is struggling to pay rent, bills and other related expenses amid thousands of dollars in loans.

Huezo said he considered moving with his family to Aurora, Colorado, this year. He earns $25 per hour but said it’s not enough to cover his $3,200 monthly rent in South Central Los Angeles.

"That was something that made me tear up, seeing all of my colleagues defending and protesting our rights,” Huezo said with emotion about the strike. "I feel proud of all of my colleagues.”

Hotel workers who spoke to NBC News said they have been taking on heavier workloads because staff shortages due to the pandemic have yet to be restored to normal levels. Tourism and business numbers are picking back up to pre-pandemic numbers in Los Angeles and Orange counties.

Lilia Sotelo, 47, a room attendant with the Sheraton Gateway, said she and her colleagues are having to take on double and sometimes triple the workload. She tends to about 13 or 14 rooms a day, the same number as before the pandemic. But with fewer staff members, the rooms are not cleaned daily, making her job tougher, she said.

“We work so hard. We deserve to have a better life with a chance to live where we work,” she said.

Huezo said: “We’re very tense. We’re working under a lot of pressure from the bosses — they’re not adding more workers that they need to.”

Maria Hernandez, a communications specialist with Unite Here, said the union's internal survey found over half of the workers who responded said they either had to move or will move in the next five years because of the rising cost of housing.

The Coordinated Bargaining Group, a coalition representing 44 hotels in Los Angeles and Orange counties, filed an unfair labor practice charge against the union the day contracts expired.

The coalition argued that the union failed to bargain "in good faith" by striking and by failing to respond to a counteroffer from the coalition, Keith Grossman, a spokesperson for the group, said in a statement. The counteroffer included wage increases of $6.25 per hour and increases of $1.50 per hour toward health care benefits over four years.

The coalition also criticized the union's support for a 7% tax fee on guests of unionized hotels and a proposed ballot measure that would rent rooms to unhoused people.

“If the Union really wanted an agreement to help the employees, it would have dropped these issues long ago instead of taking employees out on strike over them,” Grossman said in the statement.

Of the proposed tax fee the union proposed, Hernandez of Unite Here claimed hotels have no issue charging customers for "bogus" fees. The fee would go toward a workforce housing fund that would help with temporary housing, emergency loans and funding for developmental housing projects, Hernandez said.

President Joe Biden took jabs at hotels and the travel industry this year for charging customers “junk fees,” calling on Congress to crack down on them.

The Westin Bonaventure in Los Angeles, the union’s largest employer, with 600 hotel employees, was the first — and still the only — hotel to settle a deal with the union that met its conditions.

“The Westin Bonaventure is the biggest hotel [in Los Angeles]. And if they can do it with about 600 workers, what’s stopping all these other hotels from doing it, as well?” Hernandez said.

The latest strikes are the largest that have been authorized in recent years in the hotel industry. Almost 8,000 Marriott hotel workers across seven major U.S. cities, some of them in California, walked off the jobs in 2018 for two months before contract deals were settled.

Hernandez said there are still no bargaining meetings planned. She said the deal with the Westin “inspired” workers to go on strike, “proving that it’s possible.”