Evictions are piling up across the U.S. as Covid-era protections end and rents climb

WASHINGTON — On a recent Friday morning, more than 100 renters facing eviction filed through Arizona Judge Anna Huberman’s court in what’s becoming a typical day for her, as a wave of evictions hits Phoenix and other cities large and small across the country.

The vast majority of the renters that day had missed their October payments a few weeks earlier and were now at risk of being removed from their homes within days, according to the judge. One woman said her rent money that month went to pay for her mother’s funeral, a day care worker said she didn’t get paid for two weeks when her workplace temporarily shut down due to Covid, and another man said he started a new job and had yet to get his first check, Huberman said.

Eviction filings have been on the rise and were above their historical averages in half of the 1,059 counties tracked by Legal Services Corp., a federally-funded legal aid group, during either August or September. The problem is expected to get worse in the coming months as federal rental assistance money runs out and people are unable to keep pace with rising rents and decades-high inflation, according to interviews with more than a dozen housing advocates, government officials and industry experts.

“Now that rental assistance is over, and now that local moratoriums are over, we’re playing catch-up to what the pandemic did, and my biggest fear is the cliff that we’ve been all anticipating is here. From here on out, it’s going to be a very, very difficult time,” said Tim Thomas, research director at the Urban Displacement Project at the University of California, Berkeley. “I don’t want to be a doom and gloom person, but we’re probably about to see the worst of what’s about to happen.”

During the first year of the pandemic, evictions tumbled after a federal moratorium was put in place making it extremely difficult for landlords to kick out tenants for not paying rents. That moratorium was lifted in August 2021, but even without that restriction in place, the number of evictions stayed well below typical levels in most states and cities because of federal funding that provided emergency rental assistance to tenants.

But that federal money began running out in many areas this summer and the Treasury Department estimates that less than $7 billion out of a total of $46.5 billion remains available, removing the last lifeline of pandemic-era protections that more than 7 million renters have relied on.

The struggle to find affordable housing comes amid wider anxiety and pessimism Americans have around the economy, which voters have consistently ranked as a top concern ahead of next week's midterm elections. A CNBC poll in October found just 16% of voters believed the economy is “excellent” or “good,” and 59% of voters expect there will be a recession over the next 12 months.

Despite a relatively strong job market and historically low unemployment, nearly 7.8 million Americans said they were behind on their rent in October and 3 million felt they were likely to be evicted in the next two months, according to a census survey the same month. That survey found that 2.5 million people had experienced a rent increase of more than $500 over the past year.

"With inflation and the massive increases in rental prices that we've seen over the last few years, it's much worse for low-income renters than it was before the pandemic when we were already in an affordable housing crisis," said Daniel Grubbs-Donovan, a researcher at the Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

The increase in rents has begun to slow as inflation and overall economic uncertainty have more people holding off on moving, according to an analysis by Redfin. Still, rents nationwide were up 9% in September, compared to a year earlier, and more than a dozen cities had double-digit rent increases, it said.

In Phoenix, for example, rent increases have slowed in recent months, but in June were up 24% year over year, with a median asking rent of $2,261. In Maricopa County, which includes Phoenix, evictions are at their highest levels since at least 2016, with more than 45,000 filings this year.

“Lately, it just seems to be all that we’ve been doing,” said Huberman, the presiding justice of the peace for Maricopa County.

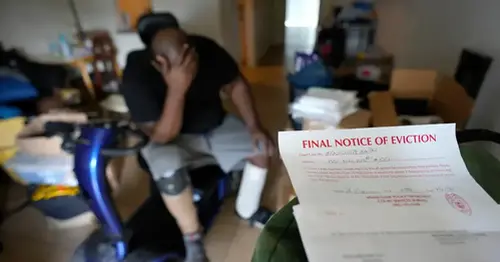

Zenovia Johnson is one of those Phoenix renters who’s been struggling to stay in her home because of rising rents. She said she missed her rent payment at the start of October and received an eviction notice from her landlord just days later. She borrowed money to cover her payment, but now is unsure how she will make November's rent with the income from her telemarketing job unable to cover her bills. Last month, her car was repossessed because she had been prioritizing her rent over her car payment.

“Everything has gone up, I just can’t keep up,” the single mother of two young children said. She added that she was not sure what she was going to do.

The Phoenix area has had some of the highest inflation in the country with prices up 13% in August compared to a year earlier, including a 14% increase in food prices and a 19% increase in housing costs. While the price of gas has fallen below $4 a gallon in most of the country, it still averages above $4.50 in Phoenix.

One region that has seen the greatest increases in housing costs is Oklahoma City, where rents were up 24% in September compared to a year earlier to an average of $1,260 a month, according to data from Redfin. Rents have been going up, in part there, because of a growing number of large out-of-state real estate investment firms buying up property in the region and raising rents, and a lack of affordable housing for lower-income families, local housing advocates said.

“Until we’re able to better match wages with housing costs, evictions are going to continue to be a problem, because with rising rents, people are having to stretch their budgets even more," said Sabine Brown a senior policy analyst at the Oklahoma Policy Institute. "One medical bill, one car repair can pretty quickly push someone towards an eviction.”

In Oklahoma County, which includes Oklahoma City, evictions have been steadily on the rise this year and are more than 40% above their pre-pandemic levels, with more than 1,800 evictions filed in September, according to data from Legal Services Corp. More than 40% of residents in the county are considered “rent burdened,” meaning they spent more than 30% of their incomes on rent.

"They’re humans and they’re families with children, and this is in Oklahoma, the heartland so to speak,” said Michael Figgins, the executive director of Legal Aid Services of Oklahoma. “It’s chronic here, just like it is in places where people seem to think this is where these actions happen, but they’re happening here too.”

Even areas seeing less dramatic increases in rent are seeing a rise in evictions as pandemic-era protections end. In Minneapolis, where rent increases have trended below the national average, evictions in September were 37% above their historical averages after shooting up in June, when the state lifted its eviction moratorium.

“I’m talking to a lot of people who are just now getting back on their feet and getting back on a decent economic footing,” said Andrea Palumbo, a housing attorney for Minnesota Home Line, a nonprofit tenant advocacy group. “I hear a lot of people saying they just need a little more time — I’m going back to work, my husband or wife is going back to work, and we’re going to get back to where we were. We just need a little more time.”

In Minnesota, it’s not just a problem isolated to major urban centers, but also rural and industrial communities, where housing costs have been on the rise as well, she said. In Clay County, a working-class community just across the state line from Fargo, North Dakota, the number of eviction filings in September were three times where they were before the pandemic. About half of the county’s 60,000 residents were having to spend more than 30% of their income on rent, according to data from the Legal Services Corp.

With the emergency rental assistance funds running low, the Biden administration is urging states and cities to use other sources of funding, including the remaining money from the Covid stimulus bill passed last year, to continue providing support to renters or to put other protection policies in place, said Gene Sperling, the White House’s coordinator for American Rescue Plan funds.

“The old status quo is not a normal we want to return to," he said. "No one should want to return to a normal where eviction is too often seen as a first resort, not a last resort, where there’s little mediation and where the overwhelming majority of tenants have no counseling or representation at all."

Sperling said that more affordable housing is the long-term solution to the struggles renters are facing, but that’s a goal that will take time and additional funding from Congress.