For Black-owned businesses, concerns extend beyond inflation, supply chain issues

When Keith Millner, wife Charmaine and two of their friends opened a Jersey Mike’s Subs sandwich shop in Atlanta in 2019, they had no idea they would end up working behind the counter.

Their doors opened in November 2019, four months before the Covid pandemic shut down the country. When businesses started reopening in July 2021, the nature of commerce had changed — and Black businesses felt the reverberations. For this group at Jersey Mike’s, part of the work became finding dedicated workers post-pandemic. With little to no options, they were forced to don aprons and hats and roll up their sleeves.

“It’s either that or close the business,” said Millner, a former commercial banker who now trains individuals and organizations on corporate culture, public speaking and other areas. “We were trained on every aspect of the business. So, yeah, we ran the counter, made sandwiches, worked the grill, ordered inventory — whatever it took. And we still do.”

A recent study of small business owners by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce found that inflation and supply chain issues are the top challenges entrepreneurs face today. However, Black business owners, like Millner and Co., face other unique hurdles that are specific to the Black community.

Unlike their white counterparts, Black businesses deal with systemic racism — a fact highlighted in a study on the government’s Payment Protection Program (PPP). The study shows that there are structural inequities “built-in to the administration of the program, the application process, and the fee structure.” Additionally, Black businesses often encounter racism and discrimination when securing bank financing, which leads to them having difficulties acquiring loans.

“We know that when something is bad for all small businesses in America, it’s worse for Black-owned businesses,” said economist Nicholas J. Hill, the Dean of the School of Business at HBCU Claflin College in Orangeburg, South Carolina. “So, if there’s any type of economic shock or supply shock, like the pandemic, it is going to hit us a lot harder.”

There has also been a massive increase of Black workers wanting flexibility instead of working traditional 9-to-6 schedules, leading to labor shortages, according to a study by Future Forum.

A Future Forum/Slack survey of 5,448 workers found that 83% of Black workers want a flexible working schedule to create a work-life balance, which creates a labor shortage for Black business owners serving the Black community, especially in the service industry. Millner’s Jersey Mike’s in Atlanta is located in an area with a largely Black demographic and workforce. Millner and his corporate executive co-partners Charmaine Ward, Eric Harrison and Nicole Williams say these stats coincide with their ongoing staffing issues.

“Their freedom and flexibility in their schedule are more important to them than a regular paycheck,” Millner said of many young Black workers he has employed. “And so, they will drive Uber or Lyft. They will take the occasional odd job or they’ll go work for a moving company for a day or two or they’ll take four roommates so that they can split their rent. They’re making a lot of different choices from a lifestyle standpoint. And it impacts business.”

The challenge of securing funding

The Chamber of Commerce study said that 85% of small business owners say they are concerned about the impact of inflation on their business, up from 74% last quarter. One in three small business owners call inflation their highest concern and 67% of them have raised prices in response to inflation. Those concerns weigh heavily on Black-owned businesses, too. But the biggest hurdle is finding those willing to finance their business.

Maya Barfield, a veterinarian who owns Willow Brook Animal Hospital in Dallas, was astounded and deflated when, despite having pristine credit and attempting to purchase an established successful business, she and her husband were refused bank loans.

“You put together a great portfolio and it’s not enough,” Barfield said. “A process that should take 30 to 45 days took us six months. It was exhausting. Our white counterparts who are on equal footing had no such problems.”

She and her husband, a pharmaceutical company executive, had to use programs such as Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC)’s Black Economic Development Fund to secure the resources to procure their business.

This concern is unique to Black entrepreneurs. A number of studies and organizations point out various discrepancies in lending practices, all of them pointing to Black entrepreneurs being denied at an exponentially higher rate than non-Blacks. The Federal Reserve found that over half of Black business owners were rejected for bank loans, which is twice the rate compared to white business owners.

The U.S. Small Business Administration’s flagship 7(a) program decreased loans to Black businesses by 35% in 2020, the largest drop in lending to any race or ethnic group tracked by the agency.

Millner and Co. had a curious experience when attempting to open their Jersey Mike’s restaurant. They received two approval letters from major banks. But days before closing, they were told they could not be funded.

“We have A-1 credit—all of us,” he said. “We had purchased equipment and the initial inventory, signed a 10-year lease and hired people. And then we had to scramble.

“I used to be a banker, so I know the drill. This was not a common practice, approving someone and then pulling the offer just before closing.”

Because they are well-connected in Atlanta, they were able to use their resources “and find alternative funding,” Millner said. “But it was incredible we had to go through that.”

Many Black businesses, the Brookings Institute’s report said, had greater luck pursuing loans from non mainstream banks. NPR reported that Savannah, Georgia’s Black-owned Carver State Bank helped many Black businesses that were denied loans from mainstream banks, issuing $9 million in PPP loans within a five-month period.

But all PPP loans have not been beneficial to Black-owned businesses. The Center for Responsible Lending stated some of those challenges in their report.

“The Paycheck Protection Program continues to be disadvantageous to smaller businesses, businesses owned by people of color, and businesses without employees. PPP loans can be forgiven if the business is able to use the funds for eligible expenses within eight weeks of receiving the loan,” the report read. “This requirement makes it challenging, particularly for very small businesses, to ensure loans are forgiven rather than converted into long-term debt.”

Non-Black support has dwindled

Black-owned businesses were energized by the response to the Black Lives Matter-led social justice movement of 2020. Inspired by the cause and frustrated with long-standing inequities that were on full display when George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, BLM helped ignite a push to support Black-owned businesses. There was no data to support the uptick in sales that owners say they initially felt, but anecdotally, they contend there was a boost once businesses reopened after the pandemic-forced shut down.

According to NBC Bay Area, searches for “Black-owned businesses near me” peaked in June 2020, with companies like Yelp making it easier for people to find and support Black-owned businesses, per data from Google.

That meant non-Black patrons were on the support train, too. “I felt it and I saw it,” said Mel Banks, who was shopping for a birthday gift for his wife last week at The New Black Wall Street in Stonecrest, Georgia, about 17 miles east of Atlanta. It is a mall that has more than 100 shops and restaurants — all Black-owned.

Banks, who lives in nearby Conyers, said he is a frequent visitor of the mall and was taken aback at the number of non-Blacks who shopped there. When the mall opened in May 2021, “White people were there buying stuff. It was mostly us — make no mistake,” he said. “But there was some white support.”

Over time, though, the enthusiasm for the BLM push diminished. And as BLM the movement quieted, so did support.

Tremaine Jasper, owner and editor of PhxSoul.com, a website that lists events and has a Phoenix-area Black-owned business directory, said he benefited from the social justice movement and community effort to support Black-owned business. He said he received up to 10,000 views in one day, when he usually had 13,000 a month. His website was promoted on mainstream media outlets, including rapper Jay-Z’s Roc Nation.

While traffic on his website has slightly dipped since then, Jasper said that he also witnessed a decline in revenue for advertising and grant funding opportunities, which were much more promoted to entrepreneurs and made available during the pandemic. He said it is difficult to pinpoint the cause for the decline, but noted one factor could be from a decline of media coverage highlighting Black-owned businesses.

“I think that PhxSoul.com has probably dropped off in the minds of people who don’t regularly visit the website,” he said.

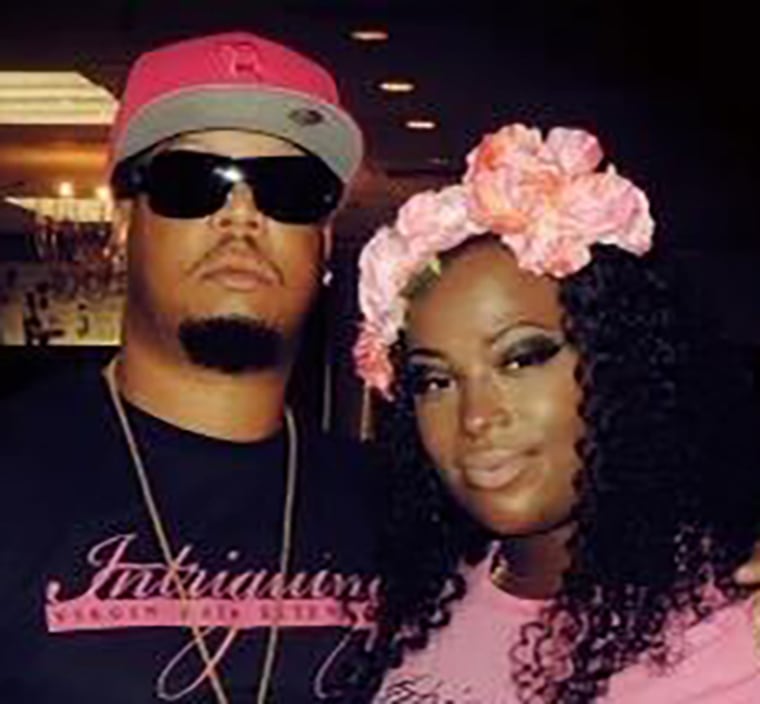

The same can be said for salon owner Nikia Londy, who runs Intriguing Hair, a wig and hair extension shop in Boston. She said that during the height of the social justice movement, corporations and financial institutions pledged to support Black-owned businesses. However, two years later, Londy, 37, said she doesn’t “really see where that has gone.”

Alternative options for Black businesses

To address the stunted growth and financial concerns of Black businesses, Steve Hall, LISC’s vice president of Small Business and Economic Development Lending and its national director of Entrepreneurs of Color Fund, said the company has also invested $250 million into its Black Economic Development Fund to alleviate some of the economic challenges in Black communities and help close the racial wealth gap.

This helped small business owners like Londy, who faced major financial challenges both during and post-pandemic. Aside from struggling to make payroll during the government shutdown, and having her store looted during the 2020 protests, Londy was denied a business loan from her bank of 10 years. Londy said her bank’s rejection “didn’t make sense,” and as a result was grateful for the alternative funding options like the ones LISC provided.

The salon owner eventually received two $10,000 grants, one from Verizon’s Small Business Digital Ready program through LISC and another from PayPal through the Association for Enterprise Opportunity, a program that provides capital and services to help underprivileged communities. Through LISC’s digital accelerator program, she also was able to hire three college interns from the Hult International School of Business, who worked on a digital marketing campaign for Intriguing Hair and helped increase customer traffic to the salon.

LISC also works with many major banks and insurance companies, and public and private foundations that invest in communities of color. Hall, who leads LISC’s small business and commercial lending, said the organization works with partners and foundations to decrease down payment risks for borrowers. The normal down payment risk for commercial real estate averages around 10-20% for borrowers, Hall said, but his organization lowers it to between 3 to 5% for borrowers.

Hall advises Black businesses to consider certain industries, like professional services, in which they have a better chance at being successful. Hall says that Black-owned businesses need to be in more sectors and should reflect the community needs. He cites “The Jeffersons,” a popular 1970s Black sitcom centered on a Black man who built wealth as a dry cleaners owner as an example of a business endeavor that Black people embraced.

“In the ‘70s and ‘80s, African Americans … we dominated the dry-cleaning business nationally,” Hall said. He said that’s not the case anymore, adding that Black American likely “didn’t see the value in it.”