Navajo Nation’s quest for water and justice arrives at the Supreme Court

NAVAJO NATION, N.M. — Her hands gripping the steering wheel, Marilyn Help-Hood gingerly drove her rugged Ford pickup truck along rutted unpaved roads, occasionally sliding in the mud, in search of one thing: water.

After a bumpy 4-mile drive in the eastern reaches of the Navajo Nation reservation in Twin Lakes, New Mexico, she arrived at her local well. Helped by her son Shane, 31, Help-Hood attached a hose to a tap at the base of the well and began filling a plastic barrel in the back of her truck with the untreated water.

Help-Hood, 66, has no running water at her small one-story home and needs to regularly replenish her supplies for drinking, cooking, washing dishes and feeding her small collection of sheep, horses and dogs. Even cleaning dishes is a complicated procedure without the benefit of turning on the tap, involving two different basins of water, one for washing and one for rinsing.

Trips like the one she made one day last week are a feature of life on the reservation, where thousands of the roughly 170,000 people who live there do not have running water.

“It’s just something that has to be done,” Help-Hood said. “It’s just part of life. It’s how we are dealing with our water situation.”

As part of the tribe’s efforts to assert control over its long-term future, it filed a long-shot lawsuit in 2003 arguing that the U.S. government has a duty to assess the nation’s water needs and ensure it has enough. After lengthy litigation, that case is now before the Supreme Court, which hears oral arguments on Monday.

For the tribe, the case is about more than what rivers it can draw water from — the Navajo say it's about ending nearly two centuries of injustice perpetuated by the federal government, which has failed to keep promises and left them to suffer on the arid lands where their ancestors settled.

In raising her five children, Help-Hood, who is a schoolteacher, said she cited the importance of the four elements of earth, wind, water and light in Navajo tradition.

“I want my children to value water. Now they have grown, they know that water has to be appreciated,” she said.

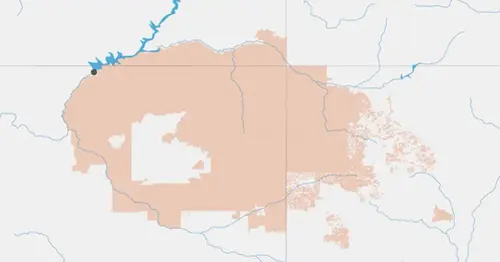

The lack of water and the infrastructure needed to pipe it across the vast reaches of the more than 17 million acre reservation — larger than the state of West Virginia — which straddles parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, remains one of the biggest challenges facing Navajo leaders.

As Help-Hood and others see it, the tribe has been relegated to secondary status in the fight over water rights in the Southwest, where states have long fought for their own pieces of the pie through complex negotiations and litigation. The scramble for water is only becoming more intense, with a decades-long drought leading to depleted supplies in the major reservoirs in the Colorado River basin, with the growing threat of climate change looming in the future.

The Colorado River, which supplies water as far afield as Southern California as well as to the surrounding states, meanders directly along the reservation’s northwestern border on its 1,400 mile route from Colorado to Mexico. And yet, the tribe has no right to draw water from the Lower Colorado River, the section starting just south of the Glen Canyon Dam in northern Arizona that then runs through the Grand Canyon.

For Crystal Tulley-Cordova, a hydrologist in the tribe’s department of water resources, water is essential to the tribe moving from “survival mode to thriving mode.”

On an exclusive tour last week of Navajo sites, Tulley-Cordova gave examples of the ways water permeates so many elements of tribal life. She cited a new housing project on the reservation in Rock Springs, New Mexico; the construction of a pipeline taking water from the San Juan River deeper into the Navajo territory; and the growing campus at Diné College, the tribe’s own institution of higher education.

“On water rights, it’s important to consider a permanent homeland. What is needed for that is resources. Not just for today’s Navajo but for future generations,” Tulley-Cordova said.

At another stop on the tour, about an hour north of Help-Hood’s home, the Litson family talked about its struggles in getting water for its cattle ranch spread out over a hillside dotted with sagebrush. Dorthea Litson, whose family has farmed there for generations, bemoaned a storm that had knocked out a windmill that powers a water well.

“It actually is a hard life,” she said. “A lot of people don’t realize how much goes into it.”

'Broken promises'

The Navajo lawsuit now before the Supreme Court rests heavily on history, going right back to 1849 when the tribe signed its first treaty with the United States at a time when European settlers were rapidly moving westward. Soon after that agreement, the federal government forced the Navajo away from their ancestral lands, moving them more than 300 miles eastward to Bosque Redondo, where they lived in wretched conditions. It was just the first of what the tribe’s lawyers refer to in court papers as a series of “broken promises.”

Eventually, the government agreed to allow the Navajo to return to their own lands, traditionally denoted by four mountain peaks the tribe consider sacred. In an 1868 treaty, federal officials said they would provide resources needed for agriculture, a pledge that lawyers for the tribe say implicitly included a right to sufficient water.

But in the intervening years, water rights to the Colorado River were divvied up between states and the federal government, with the latter tasked with representing tribal interests.

“Historically, it’s fair to say that tribes have not been at the table when these big river management decisions were being made,” said Anne Castle, a western water rights expert who serves as the federal representative on the Upper Colorado River Commission.

A 1922 compact divided the Colorado River into its upper and lower sections, and water allocation in the lower basin was addressed six years later by an act of Congress that also led to the construction of the Hoover Dam farther downstream on the Arizona-Nevada border.

Later, the issue ended up at the Supreme Court in Arizona v. California, a case concerning how water would be allocated among the states. In some form that litigation ran for decades from 1952 to 2006, leading to a series of rulings.

During the course of that case, the federal government, on behalf of Navajo Nation, asserted rights to tributaries of the Colorado River, including the Little Colorado River, which runs across the southwestern part of the reservation, but not the main channel of the Lower Colorado River.

Navajo access to the Little Colorado River is still being adjudicated in state court. With the help of the federal government, the tribe previously settled claims to water from the San Juan River, another Colorado River tributary that runs through Navajo territory in the Four Corners region, where the borders of Colorado, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico meet. The tribe can also draw some water from the Upper Colorado River basin. A previous attempt to settle Navajo claims to the Lower Colorado River failed about a decade ago.

In the current Supreme Court case, the federal government says the tribe is seeking to reopen already decided cases that determine how water in the Lower Colorado River is allocated. The tribe counters that it is not seeking a decision on those rights specifically. Instead, the tribe says that the federal government’s oversight of the entire Colorado River, as well as its duties to the tribe, mean that it is required to do a full assessment of Navajo Nation’s water rights, which may affect how water is allocated.

The tribe’s lawsuit alleged that the federal government had breached its duty “to address the extent to which the Navajo Nation needs water from the Colorado River to make its Arizona lands productive.”

Arizona-based U.S. District Court Judge Murray Snow in 2019 rejected the claim, saying the tribe had not shown that any duty of trust had been violated. He also raised questions about whether a ruling for the tribe would infringe on the Supreme Court’s findings in the long-running Arizona v. California litigation.

The San Francisco-based 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in April 2021 revived the tribe’s lawsuit, concluding that the tribe was not seeking direct access to waters of the Colorado River and the lawsuit therefore did not implicate the various Arizona v. California decisions.

“The Nation’s claim, properly understood, is an action for breach of trust — not a claim seeking judicial quantification of its water rights,” the court concluded. The appeals court went on to find that that the tribe could pursue its breach of trust claim.

The federal government and states then appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed in November to take up the case.

'Cloud of uncertainty'

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, representing the federal government, argues in court papers that the tribe has failed to point to any duty of trust that the federal government has to the tribe when it comes to providing access to water from a specific source.

“The United States has a general trust relationship with Indian tribes. But the existence of that general relationship does not itself establish any judicially enforceable duties against the United States,” she wrote.

She said that if the Supreme Court were to rule in favor of the tribe, it would force the government to violate a 1964 decision that was part of the Arizona v. California litigation. That ruling limited the circumstances in which the federal government could divert water from the Lower Colorado River.

Federal officials declined to comment on the litigation.

States involved in the case — Colorado, Arizona and Nevada — also reject the tribe’s arguments. Colorado’s lawyers said in that state’s brief that a ruling for the tribe would cause “immediate and long-term disruptions to the coordinated management of the Colorado River."

States point out they are already implementing a 2007 agreement on water shortages as well as a drought contingency plan adopted in 2019.

The states, the federal government and three water districts in California involved in the litigation all argue that a win for the tribe would implicate rights to the main channel of the Colorado River.

Rita Maguire, the lawyer arguing at the Supreme Court on behalf of the states and the California water districts in the case, said in an interview that although the tribe is now focusing on the government’s general obligation to ensure water access, “it is clear the Navajo are seeking a water right to the Lower Colorado River.”

Any change to how water is allocated “could lead to harms to other states,” she said. A ruling for the tribe would give it priority over others, and that “creates a cloud of uncertainty,” she added.

Tribal officials are aware they likely face an uphill battle at the Supreme Court, which is historically not friendly to Native Americans. Just last year the court ruled 5-4 against tribes in Oklahoma in a decision that expanded state authority over their territory.

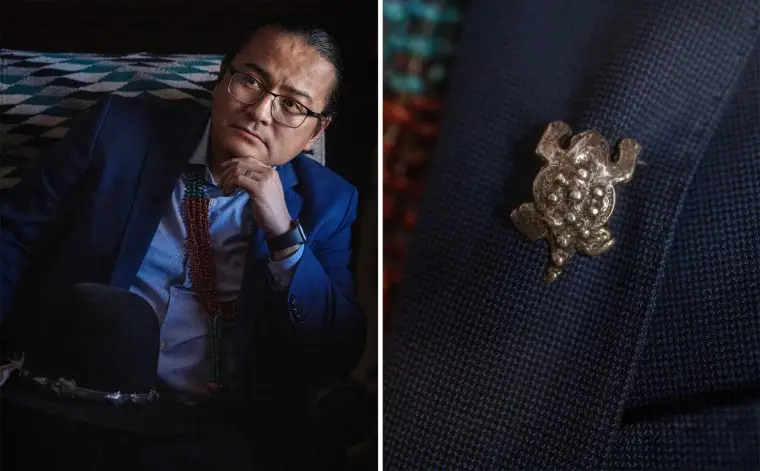

Buu Nygren, the tribe’s president, said in an interview that he is hopeful, viewing the case as a chance for the United States to hold up its side of the bargain as negotiated back in 1868.

“Keeping a group of people that have just been in tough, tough, tough, situations for decades, to continue to hold them down and keep their hands tied and one foot tied and expecting us to thrive in those scenarios is not feasible” he said. “They should cut the ropes, untie our other foot and let us run and develop.”

“We honored our end of the deal, and they just need to honor their end of the deal,” he added.

Back at the water well in Twin Lakes, Help-Hood expressed no concern about drinking untreated water, saying she has never gotten sick from it. She pledged that she would use water conservatively even if it was piped in, having grown to appreciate its scarcity.

“I can’t have fancy things like dishwashers,” she said.

But in reflecting on the tribe’s quest for better water access, Help-Hood echoed Nygren in placing that struggle firmly within the context of its torrid history with the federal government.