Ron DeSantis moves away from his previous hawkish foreign policy

When Ron DeSantis first ran for a U.S. House seat in Florida in 2012, the retired Navy officer earned the support of one of the Republican Party’s most prominent defense hawks.

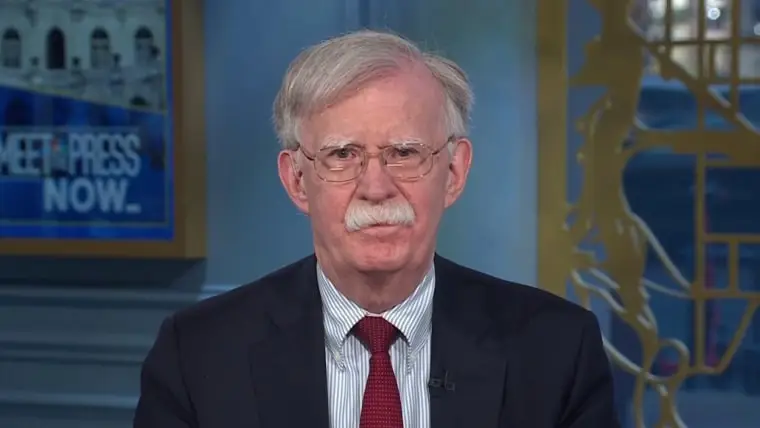

John Bolton, the former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations known for sharp elbows and a pugilistic approach to foreign policy, spoke at a Washington fundraiser for the political newcomer, who went on to win the seat. Impressed by DeSantis’ record and his understanding of “the dangers we face abroad,” Bolton would also back his re-election bids to the tune of $20,000.

Now Florida’s governor and a likely contender for president, DeSantis has begun to move away from the hawkish rhetoric that won over Bolton a decade ago and carried on through his three terms in Congress.

The most profound evidence came this week, when, in response to questions from Fox News host Tucker Carlson, DeSantis said that protecting Ukraine is not a “vital” national interest for the U.S. That position aligns DeSantis, who has not yet declared his candidacy, with former President Donald Trump at a time when the two appear to be on a collision course for the Republican nomination in 2024.

In interviews Thursday, Bolton — who is weighing a bid for president himself to stop another Trump term — said he was disappointed by DeSantis’ stance and said he is opening himself to being called a "flip-flopper" by the former president.

“The problem with trying to align yourself with Trump on any given position is his positions are very evanescent,” Bolton said. “By moving to try and mirror what Trump is saying, you may be following him for all of another week. Trump is trying out different attack lines; flip-flopper appears to be the place to start.”

“I can’t say I’ve followed every aspect of some of the things he’s done in Florida,” Bolton added. “But my impression, certainly on national security issues as governor dealing with questions in this hemisphere — Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua — he was still on the right track.”

Biden should oust '30 or 40 Russian diplomats’ in response to downed U.S. drone, Bolton says

March 16, 202308:47A DeSantis spokesperson did not answer a request for comment.

Responding to Carlson this week, DeSantis invoked several “vital national interests,” including border security and the rise of China, but said that “becoming further entangled in a territorial dispute between Ukraine and Russia is not one of them.”

Trump — leading in most polls but aware the governor is, at the moment, his strongest potential rival — noted that DeSantis took a much harder line on Ukraine in the past. In Congress, he voted for several defense bills that provided for U.S. military and intelligence support.

“It is a flip-flop,” Trump told reporters while campaigning this week in Iowa, which is scheduled to hold the first GOP presidential caucus. “He was totally different. Whatever I want, he wants.”

DeSantis cut the figure of a traditional Republican defense hawk as a member of Congress from 2013 until he resigned his seat in 2018, during his run for governor. He took a particularly hard line in support of Israel, sponsoring measures to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, limit U.S. support for Palestinians and allow states to impose their own sanctions on Iran. On the latter issue, DeSantis was a vocal critic of then-President Barack Obama’s entry into a multilateral nuclear deal that Trump later abandoned.

As a freshman lawmaker, DeSantis split with most of his party by voting against directing Obama to end the war in Afghanistan. His hawkishness was on display again in 2016, when he voted for a resolution that called on Obama to “provide Ukraine with lethal defensive weapon systems to enhance the ability of the people of Ukraine to defend their sovereign territory from the unprovoked and continuing aggression of the Russian Federation.”

While DeSantis was generally supportive of defense policy and spending bills, he broke with GOP colleagues at times on U.S. military intervention abroad, funding to maintain a Cold-War era nuclear weapon and aid for nation-building. He found himself in the minority of Republicans who tried and failed to block a nonbinding amendment that expressed support for removing Bashar Al-Assad from power in Syria in 2013. He also voted to strip funds for the B-61 nuclear bomb and reduce spending on infrastructure in Afghanistan.

By 2017, when Trump was in office and DeSantis was a subcommittee chairman on the House Foreign Affairs panel, he was asking hard questions about the U.S. mission in Afghanistan.

“Today, after more than 16 years in Afghanistan, it is not clear that things are much better than they were after the Taliban first fell,” DeSantis said at a hearing with the special inspector general overseeing U.S. programs there. “Is Afghanistan on the brink of becoming a terrorist’s dream again? Are we making the same mistakes over and over again? Should we just be done with this entire Godforsaken place? Or should we be concerned that ISIS now has a dangerous affiliate, ISIS-K, in Afghanistan that aspires to reach out and strike the U.S. homeland. How do we get this right? Or can we?”

There were other instances where the hawkish DeSantis pushed back on or clashed with Trump’s more isolationist impulses. He called on Trump in 2017 to “apply additional pressure” on the Nicolás Maduro regime after sponsoring a successful House resolution condemning "political, social, economic, and humanitarian crises" on the Venezuelan dictator’s watch. Trump, in subsequent years, would express interest in meeting with Maduro.

Also in 2017, during a House Foreign Affairs committee hearing with State Department officials, DeSantis referred to North Korean leader Kim Jong-un as a “young, plump, immature kid.” Trump indulged the dictator, holding summits with Kim and marveling about “beautiful” communications between them.

Taken together, DeSantis’ positions demonstrated a worldview that promoted the projection of American strength, particularly in defense of allies against their enemies, but allowed for limits on the use of that power.

Another announced Republican hopeful, Nikki Haley — like Bolton, a former U.S. ambassador to the U.N. — split with Trump and DeSantis this week, while mocking the Florida governor for “copying” the former president’s posture on Ukraine and serving as an “echo” not a “choice” for voters.

"Unlike other anti-American regimes, [Russia] is attempting to brutally expand by force into a neighboring pro-American country," Haley said in response to Carlson’s question about Ukraine being a vital U.S. interest. "It also regularly threatens other American allies. America is far better off with a Ukrainian victory than a Russian victory, including avoiding a wider war."

As the highest-polling alternative to Trump in a GOP primary that could feature several stridently anti-Trump candidates splitting the vote, DeSantis needs to peel away conservative votes from the former president, said one Republican strategist not affiliated with any campaign or prospective candidate. Lunging to the populist right on the issue of Ukraine could help.

“DeSantis recognizes he can’t ride moderates to victory,” said the strategist, who requested anonymity to speak candidly. “It’s a risky strategy. He’s going to lose people by doing this. The question is, Does this open the door to people he needs going forward to beat Trump?”

DeSantis' pivot away from those positions amid an anticipated presidential campaign has drawn arrows not only from rivals but from boosters, too. The editorial board of The Wall Street Journal — part of DeSantis-friendly Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. — criticized DeSantis on Wednesday for his “puzzling surrender this week to the Trumpian temptation of American retreat.”