The big problem with trying to cut spending in a debt ceiling bill

WASHINGTON — House Republicans are pushing Democrats to accept a debt ceiling bill that limits how much money Congress is allowed to spend next year.

But achieving that goal — and making it stick — would require breaking a logjam between the two parties that has persisted for over a decade: how to divvy up spending between military and domestic priorities.

Republicans want higher defense spending and Democrats want more money for nondefense programs like health care, education and help for veterans. In recent years, the two parties struck a detente: Just increase both, and everybody gets a win.

Now, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., and his conservative allies want to shatter that compact, arguing that spending is out of control. But slashing domestic funding without touching the military, as many Republicans want to do, won't fly with Democrats.

Rep. Tom Cole, R-Okla., chair of the powerful Rules Committee, said defense spending should be spared because “it’s a very dangerous world right now."

“Look, I think threats set defense spending. Domestic priorities are wants and desires, but you don’t necessarily get everything. Defense is, to me, a very different level of commitment,” he said.

Status of debt ceiling talks ‘depends on who you talk to’

May 12, 202302:58Democrats made clear they want equal treatment between the two.

“There is certain parity between defense and nondefense” spending, said Sen. Ben Cardin, D-Md. “And that’s an issue that’s important in our caucus.”

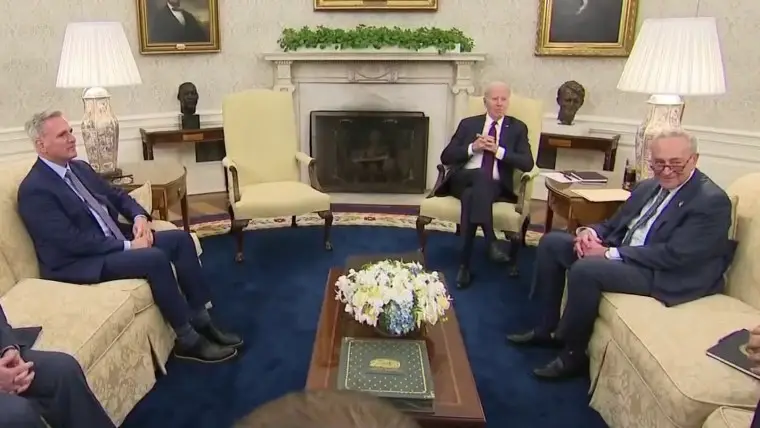

Heading into an expected meeting between President Joe Biden and congressional leaders this week, Republican lawmakers say an agreement on "spending caps" is important in securing their support to avert a dangerous debt default.

The House-passed debt ceiling bill would slash federal spending to fiscal year 2022 levels, requiring appropriators charged with allocating government funding to cut $131 billion compared with what Congress is currently spending.

Meeting that target without cutting defense funding would require a steep 17% cut to nondefense discretionary spending.

“Democrats will not let nondefense take a disproportionate share of deep cuts. So Republicans will have to moderate their cut demands if they want to spare defense,” said Brian Riedl, a former Senate Republican policy aide who now works at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative public policy think tank.

Riedl said they may be able to avoid the dispute by freezing spending rather than making cuts, suggesting “a two-year freeze” on federal spending as one possible endgame.

Republicans have avoided specifying what they'd cut, other than suggesting they could avoid cuts to military spending. When the White House argued that the House GOP's debt ceiling bill — with its lack of specificity on spending cuts — would mean harmful cuts to veterans' funding in the nondefense part of the budget, GOP leaders insisted they could spare veterans from cuts, too.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., has trashed that bill as the "Default on America Act" and insisted that the debt limit and government funding be handled independently.

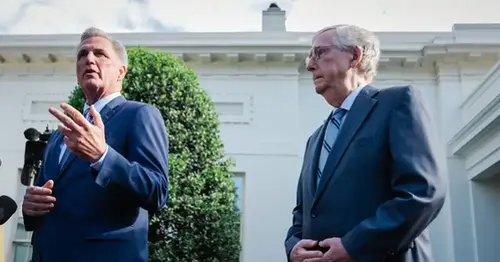

“This is too important for brinksmanship and reckless ultimatums,” Schumer wrote in a letter Friday. “White House staff, along with aides from my office, the Speaker’s office, Leader McConnell’s office, and Leader Jeffries’ office will continue to meet in an attempt to find a constructive way forward.”

McConnell is Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.; Jeffries is House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, D-N.Y.

Liam Donovan, a Republican lobbyist who analyzes legislative dynamics, said that both sides could agree to impose a spending cap for just one year. They could also agree on policy goals short of announcing an exact spending number. He suggested they could pair cuts with policies seen as creating “savings” and “growth.”

“Once you agree upon policy parameters, it becomes much more straightforward — a deal on top-line spending for at least one year, savings from unused Covid funds, a commitment to work on permitting [reform] or some other growth-oriented areas of mutual interest,” Donovan said.

Key appropriators, for now, are not involved in the talks.

“I’m leaving the negotiations up to the negotiators. I’m not involved at all in that,” said Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, vice chair of the Appropriations Committee.

Although Democrats have repeatedly said they would not negotiate on the debt ceiling, the growing fear that the U.S. could be hurtling toward disaster has prompted them to consider a parallel set of negotiations that could pair a debt limit hike with a budget deal.

“One way or the other, we have to get to ‘yes’ on the debt ceiling to avoid default. And I think there needs to be a sense of urgency,” said Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn. “I continue to believe the debt ceiling has to be addressed independently. But I also recognize that there needs to be flexibility to accommodate all of the interests and personalities — and obviously, people need to be brought together.”

Rep. Chip Roy, R-Texas, said House Republicans have "not said" specifically how they would reach their spending-cut target.

"Some of us have gone out and said that you could maintain defense spending in 2023 and return to pre-Covid 2019 spending on nondefense, and then meet our objective. We haven't said that's the gospel," Roy said.

He added that imposing a spending cap simply "leaves us with the job of doing our damn job like every family has to do" in doling out those funds in the appropriations process. "Choose what you're going to do: guns or butter?" he said.

Roy, a member of the far-right Freedom Caucus, mocked complaints from activists that steep domestic cuts could harm programs that many Americans rely on, such as affordable housing.