Tough immigration laws are putting a squeeze on home building

New home construction is key to unlocking lower housing prices. But the rate of this type of construction has fallen month to month since March 2022, and experts say tough immigration policies that have shrunk the construction workforce are behind the building squeeze.

Nationally, foreign-born people make up 30% of construction workers, data from the Census Bureau shows, making immigrants a key part of the home building puzzle. But against a backdrop of tightened immigration policies instituted during the Trump administration and exacerbated during the pandemic, the number of foreign workers entering the construction industry has almost fallen in half. There were more than 67,000 new workers in 2016, compared to 38,900 in 2020.

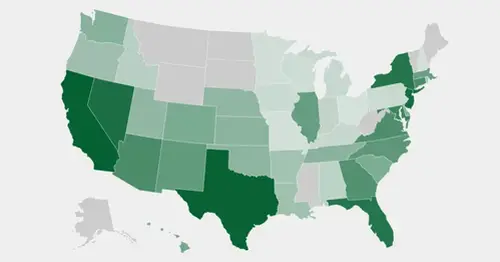

The lack of immigrant workers has led to a construction shortage, even as supply-chain stoppages and material costs have eased. NBC News compared Census Bureau data on the immigrant construction worker population in each state with a 2022 report on home underproduction by affordable housing nonprofit Up for Growth and found a strong relationship between foreign workforces and slowed home building. Specifically, for each additional 1% increase in immigrant worker share, there was a predicted corresponding increase of 6,563 in the gap between built housing units and demand for units.

“I can’t say how many times our members have said, ‘We’d bid on more work, we’d be doing more projects if we had more people to do the construction,’” said Brian Turmail, vice president of public affairs at Associated General Contractors of America, which represents home builders across the country.

While immigrants are employed in many sectors, certain fields lean more heavily on immigrant labor. This means that tighter immigration policies have an outsize effect in certain areas.

Lower immigration was a policy goal of the Trump White House, and the administration issued several policies toward that goal from 2017 to 2021, including freezing visas. The administration also took several hard stances toward undocumented immigrants, issuing executive orders for a wall along the southern border, deploying additional Border Patrol agents, and instituting the Migrant Protection Protocols, which forced asylum-seekers to stay in Mexico while waiting for hearings.

The number of new immigrant workers entering the construction industry dropped by a third in 2017 — Donald Trump’s first year in office — the first such decline in six years. And more than 2 million fewer immigrants than expected entered the labor force from March 2020 to late 2021, according to estimates from researchers Giovanni Peri and Reem Zaiour of the University of California, Davis.

Many builders said the labor strain that began in 2017 has persisted.

“As I sit here, there’s two projects that are stagnant yesterday and today because there aren’t enough [workers] for the crews to send guys there,” said Joshua Correa, a Dallas home builder. “How it was a long time ago, we didn’t have to wait — you would call and they would say, ‘We’ll be there tomorrow.’ Now it’s a month or six weeks.”

If foreign-born workers aren’t available, experts say there aren’t enough U.S.-born workers to fill in the gap.

“These [immigrant] workers are not substitutable,” said Michael Clemens, an economics professor at George Mason University. Clemens has studied the effect of immigrant labor in the workforce, and his findings refute the argument that immigrants take jobs that would otherwise be filled by U.S.-born workers. Instead, Clemens has found there’s no decrease in hiring of comparable U.S. workers, and, on average, firms that are unable to access low-skill immigrant labor slash profits 17%.

“Even when employers find a few [U.S.-born workers] to fill these jobs, they find there’s extremely high turnover in them,” Clemens said.

Immigrants, Clemens said, offer the kind of labor supply that employers in construction need to plan business activity medium- to long-term.

For consumers, that worker shortage means higher prices. Home prices, while down slightly from summer 2022 highs, are still above pre-pandemic levels. And with housing inventory in March 2023 sitting around 560,000 available units — roughly half of pre-pandemic numbers — experts don’t expect any immediate improvement.