Toxic school: How the government failed Black residents in Louisiana's 'Cancer Alley'

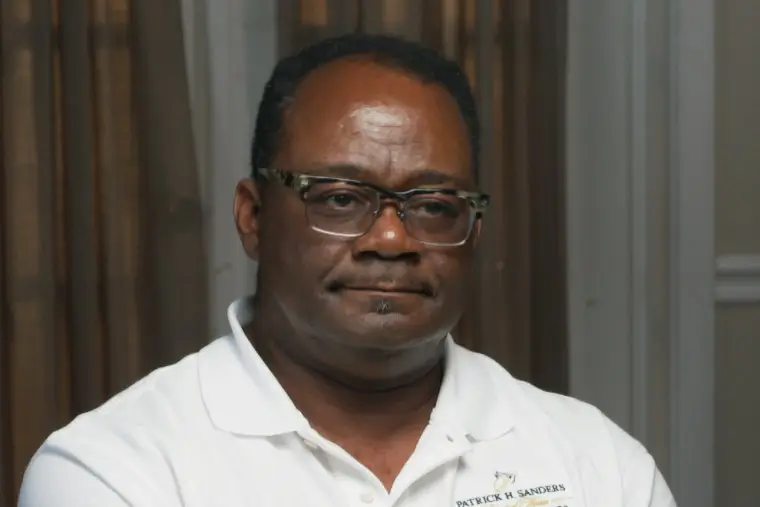

RESERVE, La. — The fond memories often give way to an intense sadness whenever Patrick Sanders thinks about the friends and neighbors he grew up with here on East 31st Street.

So many of them have died of cancer that he said he has lost count. The disease also took the lives of his father and his sister, at the age of 44. Sanders himself is facing a recurrence of prostate cancer.

His old block in this majority-Black community backs up to a synthetic rubber plant that has for decades spewed a chemical into the air that federal regulators say is likely to cause cancer.

The Environmental Protection Agency first warned of the dangers of the plant seven years ago. Yet, it has been allowed to continue to operate even though it sits about 450 feet from the Fifth Ward Elementary School.

For more on this story, tune in to NBC Nightly News with Lester Holt tonight at 6:30 p.m. ET/5:30 p.m. CT or check your local listings.

Earlier this month, the Justice Department sued the owner of the plant, Denka Performance Elastomer LLC, and demanded that it reduce emissions of the carcinogenic chemical, chloroprene. But the suit is seen by some residents and even a former agency official as too little, too late.

“EPA could have immediately shut down, but they didn’t do that,” said Steve Gilrein, a former deputy director of the EPA enforcement division that oversees Louisiana. “It’s unconscionable that it has taken this long. When the EPA suspected that this was a carcinogen, they should have acted with urgency. They just issued an order that could have and should have been issued years ago.”

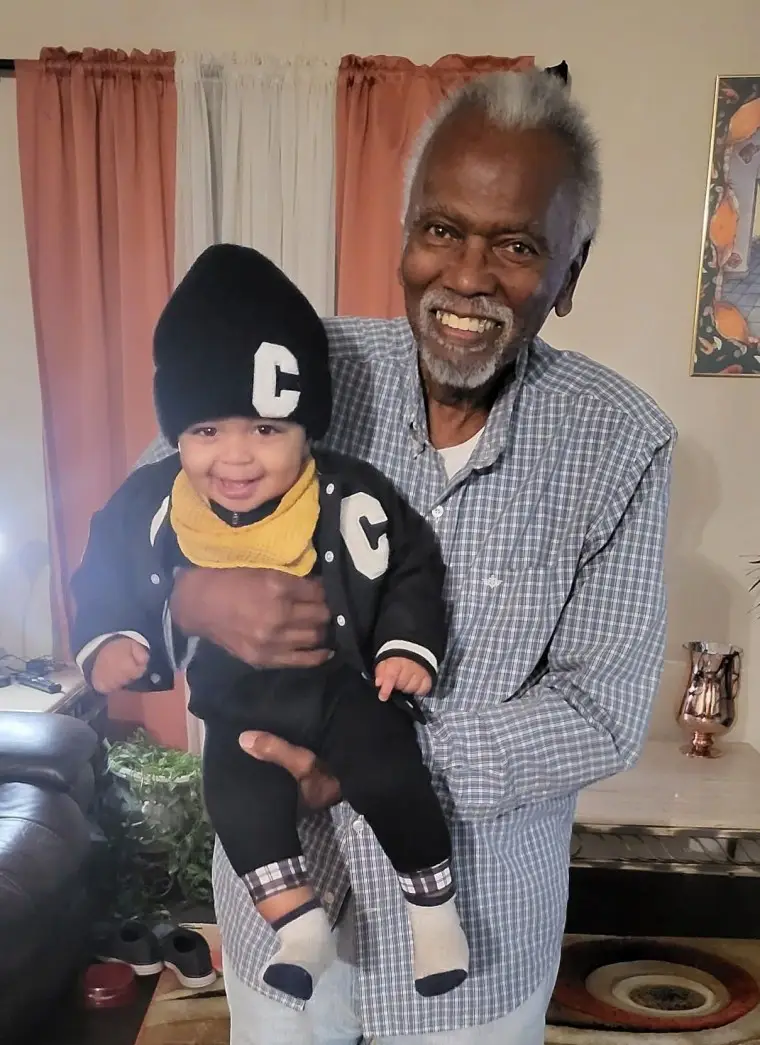

Robert Taylor, who has lived nearby for all of his 82 years, put it more bluntly.

“Why are they allowed to continue to poison us?” said Taylor, co-founder of the community group Concerned Citizens of St. John. “They need to stop until they can prove they are operating safely.”

The story of the plant is also a story of an 85-mile corridor between New Orleans and Baton Rouge now known as Cancer Alley. This town, like many others in this industrial corridor, was once home to slave plantations before scores of petrochemical companies moved in, polluting the air that fills the lungs of the mostly-Black residents.

In and around Reserve, some locals are not only pointing the finger at the lack of intervention from local and federal authorities, but they are also reflecting on whether they could have done more to protect their friends and families.

Sanders is one of them. He spent more than two decades on the district school board that oversees Fifth Ward Elementary, until he retired as president in December.

“There is a strong feeling of regret,” said Sanders, 56, who owns a funeral home. “We were making sure kids were educated, but we weren’t making sure kids were safe.”

‘A death sentence’

The 8,500-person town of Reserve sits along the Mississippi River, about 30 miles west of New Orleans.

Many of the families here live in homes that were built by their ancestors and passed down through generations. Mary Hampton, 83, said her father worked his whole life to buy a piece of land from which he gifted sections to each of his nine children.

“He thought he was leaving us a legacy,” she said. “Actually, he left us a death sentence.”

St. John the Baptist Parish had the highest cancer risk in the country for much of the past decade, according to the EPA. The risk of cancer here was about 50 times greater than the national average in 2014. Today, the cancer risk is still nearly seven times the national average, the agency says.

On a recent Monday, Hampton sat in her front yard and pointed at several nearby ranch houses as she ticked off the family members and friends she has lost to cancer.

Her son. Her brother. Her father. Her sister-in-law.

Another brother, who lives next door to the one who died, has cancer too, she said.

“We are like a bunch of guinea pigs over here,” she added.

The plant that looms over Hampton’s neighborhood was built by the DuPont company in the late 1960s. It manufactures neoprene — a synthetic rubber that can be found in products such as wetsuits, orthopedic braces and automotive belts.

For decades, DuPont produced the majority of its neoprene in Louisville, Kentucky, until the plant shut down in 2008 after public backlash over toxic air pollution.

St. John the Baptist Parish residents long worried that the emissions from the plant might be sickening the community, but they had no proof. They also didn’t have the kind of resources needed to fight a multimillion-dollar company or backing from the state.

“When it comes to Louisiana state agencies, I think a lot of it does have to do with race,” said Deena Tumeh, an attorney with the nonprofit group Earthjustice, who has been working with area residents. “Cancer Alley is one of the most extreme examples of environmental injustice that we have in this country.”

In 2010, the EPA classified chloroprene, which is used in the production of neoprene, as a “likely human carcinogen.”

Five years later, Dupont sold the plant to Denka, a Japanese chemical company. It remains the only neoprene production facility in the country.

About a month after the sale, in December 2015, the EPA published a report on its website that said St. John the Baptist Parish had the highest cancer risk in the U.S. as a result of the plant’s emissions.

But it wasn’t until July 2016 that the agency held a community meeting in the parish to warn of the dangers from the plant. That’s when Taylor founded Concerned Citizens of St. John, in large part to fight for the children to be removed from Fifth Ward Elementary.

Children under the age of 16 are particularly vulnerable to carcinogens like chloroprene, according to the EPA.

Under pressure from state regulators, Denka agreed in 2017 to install equipment designed to reduce chloroprene emissions. The company said it has reduced emissions by about 85% since 2015.

But in 2020, EPA air testing recorded spikes of chloroprene near the school that were up to 8,300% higher than the EPA’s recommended level for long-term exposure.

Denka has denied that its plant is creating a danger to the community.

“There is simply no evidence to suggest the company’s operations cause increased risk of health impacts in St. John the Baptist Parish,” a Denka spokesperson said in response to a request for comment for this article.

As community groups and environmentalists pushed for government intervention, the federal government blamed state officials for the years of inaction.

In October, the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights said in a letter that Black residents were disproportionately exposed to harmful air pollutants due to the failure of the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality and the Louisiana Department of Health to pursue stronger action.

The EPA said an investigation revealed that state agencies had downplayed the dangers of chloroprene and dismissed residents’ concerns as “fearmongering.”

It also asked the state agencies to look into whether there were safer locations to move the children of Fifth Ward Elementary.

The Louisiana Department of Health had in fact done that about four years earlier. But it ultimately determined that it didn’t make sense to move the school children to another location within the community because it wouldn’t reduce their cancer risk — an acknowledgment that no part of St. John the Baptist is free of toxic air.

Vickie Boothe, an epidemiologist and environmental engineer who worked at the EPA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for 33 years, said there was a lot of blame to go around within the state.

“It’s part of the Louisiana culture that is willing to sacrifice the residents — particularly minority and low income — in the name of the economic survival of Louisiana’s petrochemical industry,” said Boothe, who has been advising local community groups about the health impacts of airborne pollutants since retiring in 2019.

“State officials have actively dismissed concerns and ignored evidence,” she added.

Gilrein, the former EPA official, said he believes the EPA bears most of the blame.

The EPA’s criticism of the state agencies is “somewhat ridiculous because Louisiana is running the program that EPA designed, delegated to them and partially funds,” he said.

“The EPA is deflecting fire and scapegoating the state.”

An EPA spokesperson did not respond directly to Gilrein’s remarks but said “there’s no question that this community’s pressing health concerns had been overlooked by past administrations.”

The spokesperson added that the agency has taken “significant legal actions” to address the problem, citing the Justice Department’s lawsuit against Denka and an order that requires the company to “cease unsafe practices for the handling and management of harmful waste.”

The Louisiana Health Department declined to comment.

In a statement, the state Department of Environmental Quality said “the agency has, and has always had, the welfare of the community as its top priority” and that it “will continue to work with EPA and Denka to achieve the best possible result.”

‘Remember the fight’

EPA Administrator Michael Regan visited the parish in 2021 during a tour of Southern states to draw attention to how industrial pollution plagues low-income, predominantly minority communities.

Regan, who is the first Black man to hold the job, has given some people in St. John the Baptist Parish hope that the federal government will take their concerns seriously.

“The company has not moved far enough or fast enough to reduce emissions or ensure the safety of the surrounding community,” he said in a statement after the lawsuit was filed against Denka in February.

Denka has called the lawsuit “politically motivated” and said the company is “in compliance with its air permits and applicable law.” The company sued the EPA a month before the Justice Department’s lawsuit, alleging that the agency’s recommended acceptable level for chloroprene emissions is based on “outdated and erroneous science.”

While the Justice Department's lawsuit was seen by some local residents as an important step, it will bring no immediate change.

Tumeh, the Earthjustice lawyer, noted that the suit does not specify how much Denka has to reduce emissions or the time schedule. The case could drag on in court for years before the company is compelled to make any changes.

“The EPA has decided not to act fast enough to protect this community,” she said.

The EPA spokesperson said the agency took a series of actions immediately after Regan’s trip to the region, including deploying inspectors to the Denka facility to identify sources of emissions at the site.

“EPA will also propose a rule later this month that applies to chemical plants, including the Denka facility, which has the potential to deliver critical public health protections for this community and many others across the country,” the spokesperson added.

No additional details were provided.

Taylor and Hampton, who are both in their 80s, said they never imagined that they would become environmental activists so late in life. Both have great-grandchildren. They say they don’t want to see another generation exposed to toxins at Fifth Ward Elementary or anywhere else in the community

Hampton broke out in tears of joy when she learned that the Justice Department had sued Denka. But she knows the fight is far from over.