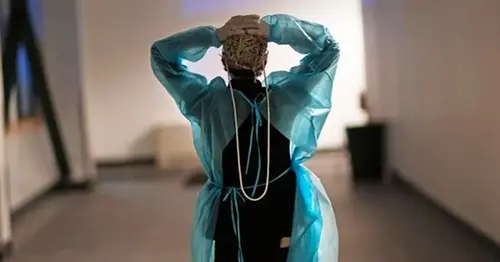

Travel nurses took high-paying jobs during Covid. But then their pay was slashed, sometimes in half.

In early 2022, Jordyn Bashford thought things were as good as they could be for a nurse amid the Covid pandemic.

A few months earlier, she had signed an agreement with a travel nurse agency called Aya Healthcare and left Canada to work at a hospital in Vancouver, Washington.

Before the end of her first shift at PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center, she said she realized other travel nurses there were earning even more than she was and asked for more money. Aya quickly amended her agreement and raised her hourly pay from $57 to $96.

In January, her rate increased again to $105 as part of a new agreement. She thought that the high pay — and a generous living stipend of nearly $1,300 per month — meant she and her fiancé could finally make plans to buy a house.

But two months later, when her assignment was renewed, Aya slashed her hourly pay back down to $56, and then cut it still more to $43.80 — less than her initial rate.

“I do know that travel nursing is fluid, and you can lose your job at any time, but I wasn’t expecting [my hourly pay] to fall 50%,” Bashford said.

The boom in travel nursing during Covid exposed a practice that has existed since the industry’s birth 50 years ago, according to experts. Nurses attracted by talk of high wages found themselves far from home with their salaries slashed at renewal time, and only then grasped the wiggle room in their signed contracts, which were really “at-will” work agreements. But the sheer number of nurses working travel jobs, and the difference between what they thought was promised and what they pocketed, has led to a substantial legal pushback by travel nurses around the country on the issue.

This summer, Stueve Siegel Hanson, a Kansas City, Missouri, law firm, filed class-action lawsuits against four travel nurse agencies: Aya, Maxim, NuWest and Cross Country. As of Dec. 27, all were still pending. Austin Moore, the lead attorney, said the suits allege the companies pulled a “bait-and-switch,” offering nurses agreements at high rates and then slashing their pay after they’ve signed. Many of the alleged incidents occurred in March and April when, as NBC News has previously reported, the demand for travel nurses, which soared during the pandemic, began to drop.

“To go take a travel assignment is a really big deal, and to get there to have the rug pulled out from under you, for someone to collapse your pay, I just think it’s unconscionable,” Moore said. “They’re on the hook for a lease, and they’re scrambling trying to find another job, and it’s a really terrible set of circumstances.”

Maxim, Cross Country and NuWest said they could not comment on pending litigation.

In a statement, Aya said allegations of bait-and-switch “are demonstrably false.”

“Travel nurse companies contract with hospitals to provide temporary staffing to help them support their communities. Nurses are the heart of healthcare and we value the nurses who work for Aya, and go above and beyond to ensure they have an exceptional experience with us.”

“As is evidenced by Ms. Bashford’s employment with Aya," the statement said, "nurses also received mid-assignment pay increases at various times during the pandemic. Further, we understand when the government reduced subsidies to hospitals following the height of the pandemic, they in turn reduced pay to travel nurses.”

$5,000 per week

Even in the industry’s earliest days, the 1970s, nurses could find themselves earning less than they expected. Advertisements touted an hourly rate of $8 to $11, but many nurses wound up making less than $6, according to Pan Travelers, a professional association of travel nurses.

Back then, there were no written agreements for the travel nurses, according to Pan Travelers. That began to change in the mid-1980s. At the same time, the number of agencies multiplied, fed by the hefty commissions that hospitals paid them.

Travel nursing became even more prevalent during Covid. Prior to the pandemic, there had already been a growing shortage of nurses nationwide, and the virus made the shortage worse. Agencies started offering nurses work agreements and renewals that extended far beyond the typical 13 weeks, according to six nurses who spoke to NBC News.

In January 2020, right before the pandemic, there were about 50,000 travel nurses nationwide, or about 1.5% of the nation’s registered nurses, according to Staffing Industry Analysts (SIA), an industry research firm. That number doubled to at least 100,000 as Covid spread, but according to SIA, the actual number at the peak of the pandemic may have been much higher.

When the pandemic was at its worst, some travel nurses were earning $5,000 or more weekly, as NBC News previously reported.

Erin Detzel never earned that much. But in November 2021, at $78 per hour, she said the money was enough to get her to move with her husband and two kids to Florida for her first-ever travel assignment.

Detzel’s 4-month-old daughter had respiratory distress syndrome and had also been hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV. That Detzel’s mother-in-law was in Florida was another inducement to move.

“We needed help,” Detzel said. “I didn’t want to put my baby in day care, so that’s kind of why we did this. My mother-in-law’s the only family member that could watch them.”

Detzel rented a house. But by February, after her first 13-week contract, Covid hospitalizations had waned and the demand for travel nurses had fallen. Her hourly pay was decreased to $62. Then it dropped again, to $32.50.

Travel nurses are typically hired by recruiters via phone calls or posts on social media and in online forums, and according to the 11 nurses NBC News spoke to around the country, the recruiters often use words like “contract.” All but one said it’s the norm for the recruiter to name a price.

Bashford said she found her recruiter through an online travel nursing forum. She said she sought out Aya’s job postings, with advertised payment amounts, on its website after a recruiter started corresponding with her.

Detzel said she agreed to go on an initial 13-week assignment from AB Staffing, an agency that is not named in the lawsuits, after a recruiter cold-called her and told her what she’d be making.

In a sample of four recruiting posts in a nursing Facebook group from 2022 from three of the agencies that are being sued, two from Maxim and Cross Country used the word contract, while two from Maxim and NuWest didn’t. The posts gave specific terms for how long the nurses were needed, as well as pay, hours, and room-and-board stipend. The two that mentioned contracts, however, used that word generally or in connection with the duration of the job, not the rate of pay. There were no Aya recruiting posts in the forum in the timespan sampled.

In the travel nurse industry, hospitals have the leverage to push the agencies for pay cuts when their demand dips, said Robert Longyear, vice president of digital health and innovation at Wanderly, a health care technology firm for staffing.

Hospitals and agencies have written agreements that allow for fluctuation, Longyear said. On top of the nurse’s agreed salary, the hospitals are also paying the agencies commissions that can reach 40%, according to a spokesperson for the American Health Care Association, which represents long-term care providers.

Given the costs, when there are fewer patients, or less demand, hospitals will go back to travel agencies and tell them they’re exercising their option to decrease nurses’ pay, and then agencies will tell the nurses their pay has been reduced.

The recruiters were the first to deliver the news about pay cuts to Bashford and Detzel.

Bashford said she got the news about her second cut the same way. “I received a text from my recruiter saying, you know, your rate got decreased even lower,” she recalled.

If a nurse balks, Longyear said, “The agency can say, ‘Hey, look, I’m going to cancel this job. If you want to keep working, this is the new rate.’”

He said this is a long-established practice, but that the pay cuts are just more noticeable now that travel nurses are promised more and paid more. And he said that because so many nurses are pursuing more lucrative assignments, it might be more common for agencies to start someone off high and then slash their pay mid-assignment.

‘At will’

When a travel nurse takes a job, the contract the nurse signs is an “at-will” work agreement.

NBC News reviewed Detzel’s AB Staffing work agreement, Aya agreements for three nurses, including Bashford’s, as well as versions of Cross Country and NuWest work agreements and the August 2021 Cross Country terms and conditions handbook. All mention the adjustable nature of work conditions. Cross Country and Aya explicitly mention “at-will” employment, which means an employer may terminate, and an employee may leave, a position at any time. The NuWest agreement explains the employee can be terminated at any time without saying “at-will.”

Bashford received emails saying, “Congratulations! Your contract was extended” from her recruiter each time she was approved for another 13 weeks, but she also had to sign new agreements with changed rates, including the cut to $43.80.

Moore, who is representing the nurses, said, “I doubt a nurse has ever successfully negotiated [the at-will provisions of] one of these contracts. They are form agreements and the agencies don’t change their terms.”

Richard Brooks, a visiting professor at Yale Law School, said some courts might view a company presenting the option between a sudden pay decrease or termination as within the realm of legality for at-will employment, depending on state contract laws.

Brooks and other legal experts said the nurses still have some avenues of redress to pursue, however.

Sachin Pandya, a law professor at University of Connecticut School of Law, said that an at-will clause affects “the probability that the employer can change terms and conditions without violating state contract law.” He said the clause might not matter for legal claims that, by their change in pay, the employer violated some other source of law like fraud or wage-and-hour statutes.

Avery Katz, a professor at Columbia Law School, adds that the language in a contract “is not the end of the story.”

“Even if there’s a contract, even if the contract says I have no right to recover, you made me these promises,” Katz said. “And then I relied on them by picking up and moving to another state and renting an apartment.”

Aya said that Bashford’s experience shows that nurses are able to negotiate the terms of their employment, and that “the harmful gist of [Bashford’s] accusations — that the company greatly lowered her pay below what she reasonably expected from the outset — is simply not true.”

‘You can’t afford to lose me’

Jordyn Bashford and Erin Detzel are both former travel nurses now.

Detzel moved her family back to Ohio. She said the hospital and travel agency treated her like the equipment in hospital stockrooms. “It’s almost like I was a supply,” she said.

AB Staffing did not respond to a request for comment.

Bashford, now a staff nurse at a different hospital in Washington, recalls bonding with her teammates during the most challenging days of the pandemic, but also the long hours and how she was effectively training newcomers on the job. With six years of nursing experience, two of them in the ICU, she said she was one of the most experienced nurses on her floor some days, which she found shocking.

But what most bothered her, like Detzel, was being made to feel disposable.