Warehouses are booming as summers heat up and safety rules lag

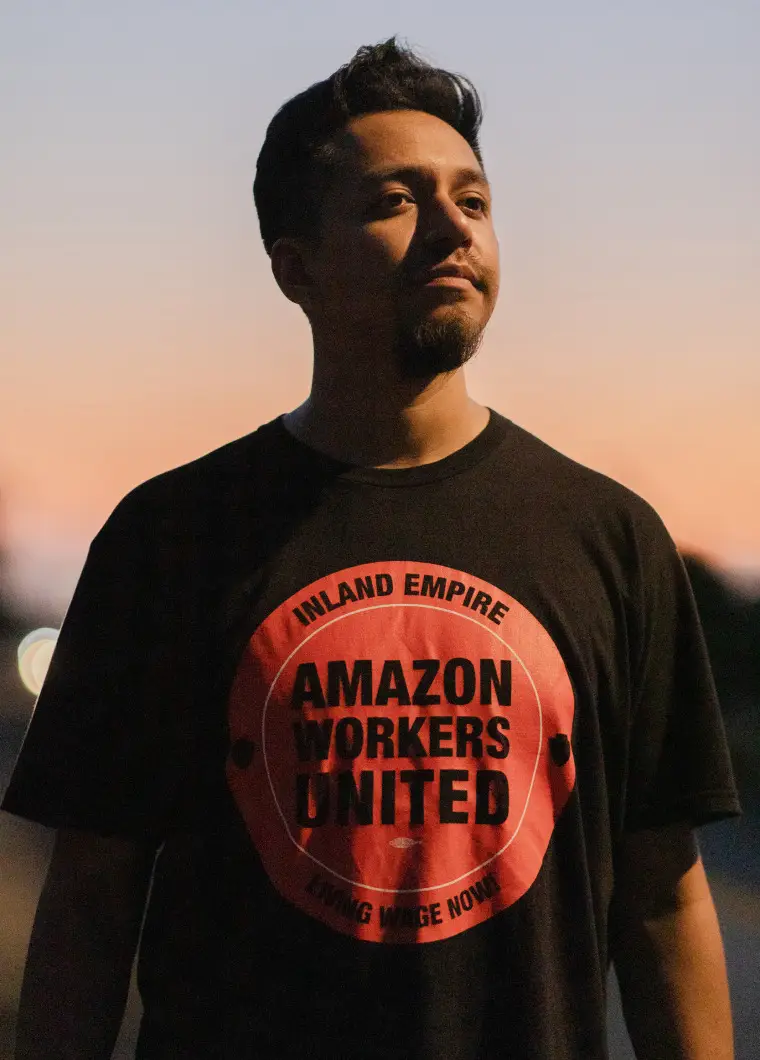

Daniel Rivera was soaked in sweat when he got into his car in San Bernardino, California, one evening last month. The outside temperature was finally dropping below 100 degrees as he turned on the air conditioning. At first, it didn’t feel much different than standing near the fans by the loading docks at the Amazon air hub where he’d just spent 10 hours moving pallets.

That week had seen triple-digit highs as a climate change-fueled heat wave smashed two months of global records. This summer is Rivera’s third at the warehouse, but he wondered whether he could handle a fourth.

“The way they’re pressing their associates, combined with the extreme heat,” he said, a cold water bottle against his forehead, “it’s just due for a disaster.”

Two months earlier, Rivera had pleaded with regulators at a workplace safety hearing to finally implement the indoor heat protections state lawmakers enacted in 2016. While California is still on track to becoming the third state to impose such standards, rulemaking has taken nearly seven years. The state has seen its four hottest summers in that time.

Rivera is among the roughly 1.8 million people who work in U.S. warehouses where fast-paced physical tasks like loading boxes can raise body temperatures to dangerous levels that many climate-control systems struggle to counter, researchers, advocates and authorities say. As e-commerce hastens a warehousing boom in some of the hottest parts of the country, regulations have lagged behind workplace heat risks that range from mild to deadly.

“We were concerned about heat with outdoor workers at the beginning of the Obama administration,” said Debbie Berkowitz, who served within it as a senior official for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. “But as time went on, it was clear that indoor workers were suffering from heat stress,” too.

Washington is taking greater note. The Biden administration issued heat safety orders last month, and Democrats recently advanced new workplace protections. Union efforts, including a UPS labor deal set to air-condition vehicles for the first time, have added momentum. But as the 2024 presidential campaign revs up, policy efforts risk slowing even as the climate crisis intensifies.

“It’s heartbreaking to come in to work to hear that another co-worker, a potential friend, has fainted or needed medical attention from heat exhaustion,” Rivera said at the May hearing. “It’s a cycle that’s not going to stop until we put a real standard in place.”

Amazon has long disputed allegations that its warehouse employees are overworked or that conditions are unsafe and said the San Bernardino site hasn’t had a work-related heat illness this year.

Workplaces built for things, not people

The U.S. warehouse workforce nearly doubled between 2017 and 2022, making cavernous steel structures a much more common workplace at a time when offices have taken the opposite course.

In the years before the pandemic, between 300 million and 400 million square feet of warehouse space was under construction per quarter, according to the commercial real-estate research firm CoStar. That rate surged to 900 million by last year. Today, warehouses blanket 20 billion square feet of the country, up about 20% from a decade ago.

“The rise of e-commerce has been the main driver of the expansion of distribution centers,” said Adrian Ponsen, director of U.S. industrial analytics at CoStar. “If you want to be able to deliver goods to households’ doorstep within two days of them placing the order, then that means you need to have large facilities holding a lot of inventory on hand within a two-day drive of all of your customers.”

Covid-19 accelerated the trend, as demand for physical goods surged during lockdowns and global supply chains buckled under the pressure. As the economy reopened, many U.S. businesses reconfigured their logistics, bringing some far-flung operations home.

The average U.S. warehouse measures about 36,300 square feet, up nearly 15% from a decade ago, according to CoStar. Newer ones are far bigger, with 30-to-40-foot ceilings and footprints of “10 to 20 football fields,” Ponsen said. “It’s almost like air conditioning an entire farm,” he said of the challenge of doing so.

Robust cooling measures are usually reserved for perishables like produce or medicines.

“When the space is for food, they maintain warehouses at a certain temperature because the government checks to make sure the food doesn’t spoil,” veteran warehouse worker Victor Ramirez said in Spanish.

When the space is for food, they maintain warehouses at a certain temperature.

— Victor Ramirez, longtime california warehouse worker

Of the 10 warehouses across California’s Inland Empire where he has worked since 2004, Ramirez recalled one with air conditioning in the work area: a major retailer facility that handled frozen and refrigerated products, where even delivery containers were kept out of the sun. His current workplace is a packaging company facility that feels cool only in the break area.

Many facilities are prone to hot spots, particularly on upper levels and by loading dock doors, according to workers, regulators and industry experts. Common climate-control measures like fans can improve air flow but usually don’t reduce internal temperatures much. Even in warehouses with cooling systems, some indoor areas can exceed 80 degrees on hot days.

One week last summer when outdoor highs ranged from 106 to 112 degrees in San Bernardino, workers at the Amazon air hub measured indoor temperatures as high as 89, according to a report by the Warehouse Worker Resource Center, a nonprofit advocacy group in the Inland Empire.

Amazon disputed the readings, saying indoor temperatures didn’t surpass 78 degrees that week or 77 degrees in Rivera’s work area the day he spoke with NBC News. The San Bernardino site is “temperature controlled with full air conditioning,” according to Maureen Lynch Vogel, a company spokesperson.

“Our heat-related safety protocols are robust and often exceed industry standards and federal OSHA guidance,” she said. “Amazon is one of only a few companies in the industry to have installed climate control systems in our fulfillment centers and at every air hub,” including the San Bernardino one, she said.

We are in an 'era of global boiling' as nearly half of all people in the U.S. are under heat advisories

July 29, 202306:17Nonbinding federal guidelines warn that heat-related illnesses become risky for those doing “strenuous work” when the “wet bulb globe temperature” — a metric that factors in humidity, wind speed and radiant heat from sunlight and machinery — passes 77 degrees. California’s proposed indoor heat rule would kick in at 82 degrees.

Of the five fastest-growing warehouse construction markets — Dallas, the Inland Empire, Houston, Chicago and Atlanta, respectively, according to CoStar — four are in the Sun Belt, which has seen both rapid population growth and scorching heat in recent years. The demographic influx has required more inventory space to serve retail customers, often in spread-out areas with large parcels of undeveloped land, CoStar’s Ponsen said.

Albertsons, Amazon, Lowes, Marshalls, Target, Walmart and other major brands all operate out of massive warehouses exceeding 1 million square feet in the Atlanta, Dallas, Houston or Phoenix areas — some in more than one of those markets — according to the research firm Predik Data-Driven.

While Amazon built the San Bernardino facility where Rivera works, many companies that use warehouse space frequently rent it from others, and CoStar data shows tenants pay for electricity in more than 95% of industrial leases signed this year.

“Someone’s looking for: What’s the least costly way to create a space to store my goods?” said Barton James, CEO of Air Conditioning Contractors of America, an HVAC-focused trade group.

Many warehouse HVACs are retrofits that require navigating workplace safety regulations, and some climate-control systems produce moisture that can damage or rust equipment if not installed properly, James said. Taken together, these factors mean investments in cooling often “take a long time to pencil out,” he said.

Other low-cost, well-established measures — like access to water, rest periods and cool zones — can make a difference for workers, said Thomas Bernard, a public health professor at the University of South Florida who has helped employers develop heat-stress management programs. Asked during a 2019 congressional hearing about the costs of doing so, he estimated it “on the order of implementing any other health and safety program.”

A long, hot wait

Back in 2012, Ramirez was working at a Walmart warehouse when he joined colleagues from a Walmart supplier’s distribution center nearby for part of a six-day march from Ontario, California, to Los Angeles to protest heat-related working conditions at the latter facility.

A decade later, he rallied with Inland Empire Amazon Workers United, a group that includes Rivera and many of his co-workers, when they walked out of the San Bernardino hub last summer, demanding higher pay and better relief from the heat.

“Taking care of associates is always a top priority,” said a Walmart spokesperson, noting that the workers who marched 11 years ago didn’t work directly for the company and that Walmart has long offered heat illness prevention training that remains “an ongoing focus.”

It’s not just temperature that you have to be concerned about; it’s also the nature of the work.

— Debbie Berkowitz, former senior OSHA official

Getting employers to institute more rest time on hot days has always been the biggest challenge, Ramirez said: “Stopping for five minutes every hour so that people can relax and go in the cool air, then go back to work — that’s what we’re fighting for.”

The warehousing sector’s injury rate has grown in the past decade, in some areas hitting levels more than twice that of private industry overall. Regulators, labor advocates and investigators have faulted the pace and production quotas many warehouse workers face, among other factors. A California law limiting such quotas took effect last year, and Minnesota passed a similar bill this year. Last month OSHA announced a national warehouse “emphasis program” over injury rates that will increase inspections, including examining heat exposure.

“Indoor workplaces that are the most dangerous for heat are those where it’s not just temperature that you have to be concerned about; it’s also the nature of the work,” said Berkowitz, the former OSHA official.

Few warehouse operators have faced as much scrutiny over injury concerns, heat-related or otherwise, as Amazon. State and federal regulators have fined the company for warehouse safety violations in recent years. Federal prosecutors are examining “possible fraudulent conduct designed to hide injuries from OSHA and others.” Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) began investigating Amazon’s warehouse practices in June, citing productivity rates and employee tracking as alleged contributors to “dangerous and illegal conditions.”

Lynch Vogel, the Amazon spokesperson, disputed Sanders’ allegations and the basis for the federal probe. She said Amazon doesn’t have fixed quotas and already offers workers “informal breaks” in addition to regularly scheduled ones, adding, “We are committed to continuous improvement when it comes to communicating with and listening to our employees and providing them with the resources they need to be successful.”

Research shows that workplace injury rates rise with temperatures and that heat slows productivity, costing the global economy billions of labor hours each year. Those effects are strongest in physically demanding jobs, both indoors and out. Studies have found workers lose as much as half their work capacity in certain environments above 90 degrees.

Alternative ways of working more safely and productively are already practiced outside the warehousing industry. U.S. Army guidelines for wet bulb globe temperatures above 90 degrees dictate 20 minutes on, 40 minutes off for moderate work, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommending similar cycles.

“It’s very easy to get to the point where your worker productivity is far less than what it would have been if you had just given them a 10-minute break,” said Juley Fulcher, a worker health and safety advocate at Public Citizen, a nonprofit organization that has repeatedly petitioned OSHA to create a national heat standard. “Employers aren’t really recognizing how much it costs them.”

It’s very easy to get to the point where your worker productivity is far less than what it would have been if you had just given them a 10-minute break.

— Juley Fulcher, WOrker Health and Safety Advocate at Public Citizen

Current federal workplace heat requirements are minimal, falling under a broad “general duty clause,” though OSHA has made the issue a top priority through several initiatives such as an emphasis program that boosted inspections over the past 16 months for industries deemed high-risk, including warehousing. The agency has conducted more than 1,900 heat-related inspections since April 2022, up nearly tenfold from fiscal 2021.

OSHA has also begun to create a heat risk prevention rule that would enable stronger and more proactive enforcement, but regulatory experts expect that to take years. Republicans have shown less eagerness than Democrats to tighten rules on employers, citing the risk of crimping business. With a divided Congress and the White House in play next year, finalizing stronger national protections by next summer could be tough.

In the meantime, “OSHA’s hands are tied by the lack of resources and a weak law requiring so many steps to issue a standard that is very basic,” said Berkowitz.

Since it began increasing heat inspections, OSHA has issued seven warnings, called "hazard alert letters," to warehousing and storage companies but no citations or fines, a spokesperson said.

“We will continue to use all the tools in our toolbox to ensure all workers have the health and safety protections they need and deserve in all workplaces,” OSHA chief Doug Parker said in a statement.

It’s not surprising that fines haven’t risen on par with inspections, said David Michaels, a George Washington University public health professor who served as the Obama administration’s OSHA director. Heat-related fines require the agency to show that “the environment is recognized as a significant hazard and that it could cause or likely cause death or serious physical harm, and that there’s a feasible method to abate that hazard,” he said. “That’s a pretty high bar.”

Although federal and California rulemaking has dragged on, two states moved swiftly after the Pacific Northwest heat dome two years ago. Washington created an emergency outdoor worker standard in July 2021, and its final version took effect last month. Oregon, which began developing a heat standard the year before, issued temporary heat rules that summer, with final ones covering all workers taking effect in May 2022. It’s the only state with protections for both indoor and outdoor workers.

Asked about its timeline, Cal/OSHA cited a “complex” regulatory process “that requires in-depth scientific, economic and fiscal research and analysis” and said a heat standard could take effect in time for next summer if the standards board Rivera testified before approves it, in a vote expected in the first quarter of 2024.

Source: https://www.nbcnews.com/investigations/warehouse-workers-extreme-heat-illness-osha-rcna95936